Yoga Book Club: Yoga Body Revisited

Sundays, June 7 - July 5, 2020

5:00 PM (UK); 12:00 PM (ET); 09:00 AM (PT)

Sundays, June 7 - July 5, 2020

5:00 PM (UK); 12:00 PM (ET); 09:00 AM (PT)

Sundays, June 7 - July 5, 2020

5:00 PM (UK); 12:00 PM (ET); 09:00 AM (PT)

Reading Yoga Body, 10 Years Later

An online study group with Daniel Simpson

Sundays, June 7 - July 5, 2020

5:00 - 6:00 PM (UK)

Modern yoga is synonymous with postures. Not all of these are ancient. Some are recent inventions. Just how radically have practices changed? What made yoga more physical in early 20th century India? Was it based on tradition, or were some things adapted from different disciplines?

Mark Singleton’s book Yoga Body explores these questions. When first published in 2010, it seemed controversial. Some of its subtleties were lost on practitioners, who often dismissed it — without having read it — as claiming that yoga was a mix of gymnastics and military training.

Others picked holes in the author’s focus on Ashtanga Vinyasa, whose claims to antiquity his work undermined. There were also objections to the choice of subtitle, since The Origins of Modern Posture Practice could be read as suggesting that nothing was old.

As Singleton explained in a later introduction: “the book does not really deal with the origins of yoga, in the sense of ultimate beginnings, but with certain of its contexts.” However, his publisher “did not wish to use the title of the Ph.D thesis out of which this book grew, ‘The Body at the Centre: Contexts of Postural Yoga in the Modern Age’.”

Despite what some readers assume, it was never his aim to “debunk” modern practice. Nor was it to argue that traditions were bogus. Many critics hold one of two views: either “we need to get rid of recent, bastardised forms of modern yoga and return to the ancient and authentic source,” or “since yoga is simply a construct, we can (and indeed should) be completely free to innovate in whatever way we see fit.” Could both be mistaken?

Reading Yoga Body over five weekly sessions, we’ll reflect on the book and how people received it. We’ll also look at new research on the history of postures, and whether it matters where practices come from. To prepare for each session, we’ll read two chapters - plus some supplementary sources that add further context. See below for more details.

Yoga Curl (Marilyn Monroe), John Kobal Foundation, 1948

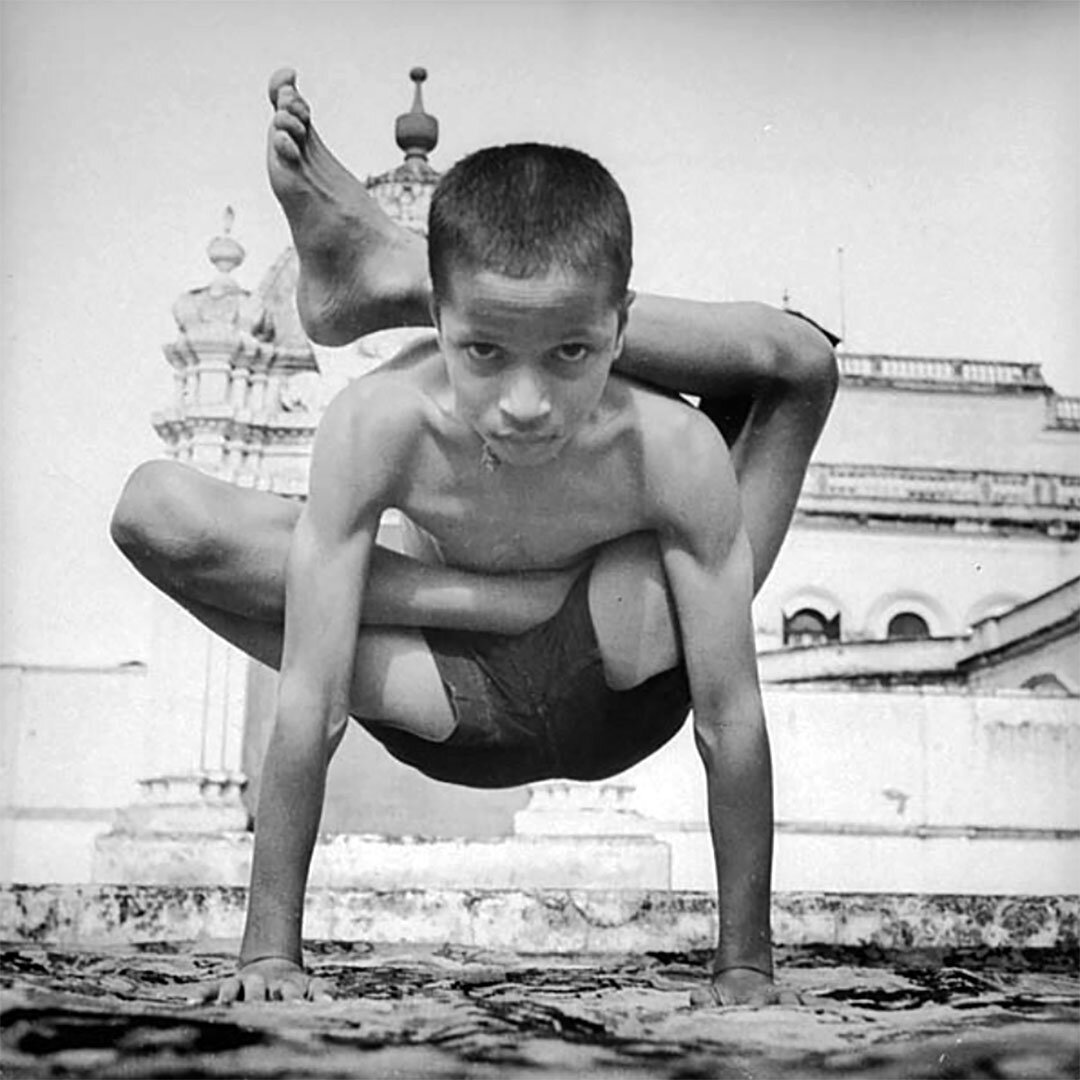

Virancyasana (T.R.S. Sharma), Wallace Kirkland, Life, 1940

Format

We meet using Zoom, a free online video app. The discussion is interactive, and everyone is free to contribute however they wish.

You can also ask questions by email, or in a private Facebook group. If you’re unable to join us live, recordings are available to catch up later.

We start at 5:00 PM, UK time (12:00 PM in New York and 09:00 AM in California), and sessions last an hour - or slightly longer if needed.

Week 1 - HISTORICAL CONTEXT

June 7, 2020

As the introduction puts it: “This book investigates the rise to prominence of asana (posture) in modern, transnational yoga.” Following a summary of its main ideas, the opening chapter presents “A Brief Overview of Yoga in the Indian Tradition.” Scholars questioned its contents, including James Mallinson, who said “it is implied that asana practice was of little importance in the pre-modern era but our sources in fact suggest otherwise.” The two later joined forces to write Roots of Yoga, which drew on more than a hundred traditional texts.

Week 2 - BAD REPUTATIONS

June 14, 2020

Chapter two explores colonial disdain for traditional practitioners. Part of this was down to suspicion, but also due to fear of “highly organised” and “militarised” ascetics, who “controlled trade routes across Northern India, becoming so powerful in the eighteenth century as to be able to challenge the economic and political hegemony of the East India Company.” The most acceptable role for the yogi was as a performer. Some even staged foreign tours, as discussed in chapter three, fuelling occult fascination with Indian traditions.

Week 3 - EMBRACING THE BODY

June 21, 2020

In many ways, modern postural yoga developed in parallel with “physical culture” — an early generic term for exercise. Some Indian teachers combined yogic methods with lifting weights. Others used the jargon of health and fitness. As Singleton puts it: “The forms of physical practice that predominate in popular international yoga today were developed in a climate of intense experimentation.” As resistance to British rule mounted, the goal was “a suitable regimen for Indian bodies and minds” that built strength and restored national pride.

Week 4 - ALTERNATIVE INFLUENCES

June 28, 2020

Chapters six and seven highlight ways in which two different disciplines shaped new ideas about physical practice — hyper-masculine body-building and spiritual systems of “harmonial gymnastics” and esoteric dance. The latter were popular workouts with Western women and also influenced Indian teachers. “In many ways,” Singleton wrote later, “the typical transnational Hatha Yoga class of today arguably owes more to these traditions of women’s gymnastics than it does to the hatha yoga systems handed down in the history of India.”

Week 5 - POSTURAL FOCUS

July 5, 2020

The last two chapters explore how photography changed ideas about postural practice, and how it was promoted. Public demonstrations were also part of how Krishnamacharya revived interest in yoga in the 1930s. As a teacher in Mysore, his students included two influential gurus of postural yoga: B.K.S. Iyengar and K. Pattabhi Jois, who taught the flowing sequences known as Ashtanga. As Singleton argues, Krishnamacharya’s approach was “a powerful synthesis of Western and Indian modes of physical culture,” presented traditionally.

About the Facilitator

Daniel Simpson presents yogic texts in accessible ways.

He teaches courses on yoga philosophy at the Oxford Centre for Hindu Studies, at Triyoga in London, and on teacher trainings.

He holds a Master’s degree from SOAS, University of London, where he studied with some of the world’s leading scholars of yoga.

He is also a devoted practitioner, having first encountered yoga in India in the 1990s. His practical guidebook to yoga philosophy will be published soon.

Endorsements

Student feedback from previous courses.

“A brilliant teacher: knowledgeable and very inclusive.”

“Daniel has made this material come to life... I was inspired.”

“Maybe the best yoga money I have ever spent.”