Light On Journalism

News As If People Mattered: A Review Essay

By Daniel Simpson

• Guardians of Power: The Myth of the Liberal Media by David Edwards and David Cromwell, Pluto Press, January 2006

• Letters to a Young Journalist by Samuel G. Freedman, Basic Books, May 2006

• My Trade: A Short History of British Journalism by Andrew Marr, Pan, July 2005

• Scoop by Evelyn Waugh, Penguin Modern Classics, August 2003 [First published 1938]

The first law of journalism, dictated to scribes down the ages, is to tell us something we don't already know. "News," quoth Corker, the archetypal hack of Evelyn Waugh's Fleet Street satire Scoop, "is what a chap who doesn't care much about anything wants to read. And it's only news until he's read it. After that it's dead. We're paid to supply news. If someone else has sent a story before us, our story isn't news."

This adage from a bygone era of copy boys and hot metal printing lost none of its currency with the advent of videophones, satellite trucks and all the rest of the panoply of gizmos that consigned telegrams to the same historical dustbin as the quaint cablese in which they were written. If anything, its tyranny holds fiercer sway than ever. The quest for novelty, no matter how trivial or tangential to everyday life, preoccupies even the most jaded and deskbound reporter as he scuttles from fax machine to inbox in pursuit of hitherto untransmitted revelations, embellishing the quotidian for the apathetic with the requisite sexing up. Few ever stop to ask why.

That journalists subsist on a diet of innuendo and intricate misrepresentation, or as Waugh put it seven decades ago, "the luscious, detailed inventions that composed contemporary history", is so widely held to be true in these days of instant refutation by blogger that it scarcely merits a mention in the news-in-brief section. To the doyens of the press corps, however, it remains anathema, regardless of how readily they devour Scoop and all its barbs. Lubricated by alcohol, and out of earshot of the customers, they may give voice to occasional doubts about the ethics of their trade, but such moments of weakness are soon drowned out by old war stories and gripes about their employers. For all their pretensions to fearless truthseeking, the task of telling it like it is about the news business is left to satirists like Waugh, his fortnightly imitators in the pages of Private Eye and an ever-widening circle of media critics, most of whom are confined to cyberspace.

Today's jobbing journalist has little time for searching questions about what ought to be newsworthy; with websites to refresh and round-the-clock schedules to fill, rolling deadlines have become the norm and product-peddling the professional imperative. As competitors converge on a common agenda for fear of losing market share, rival brands report the same stories with only the most minor variations in "angle", lapping up the tsunami of rent-a-quotes, spin doctors and public relations executives that floods the average newsroom with press releases. A fixation on access to powerful sources skews the news to focus on their words while rigid conceptions of balance protect them from systematic scrutiny of their actions. Truly investigative journalism is a rarity; managers prefer to pump money into cheaper and more dependable sources of revenue: opinionated punditry, lifestyle features and celebrity tittle-tattle. The bottom line trumps all other considerations, even the cherished journalistic clichés of leaving no stone unturned and shining lights into dark places. "We are a capitalist company providing capitalist news," stresses an editor at Reuters, a global media conglomerate, which subsidises foreign reporting by selling trading systems to banks. "We do not go in for campaigning."

So entrenched are the structural constraints that deter corporate media from serving as more effective watchdogs over the powerful, or guides to the way the world works, that attempts to discuss them are alternately derided as cynical and idealist. Exceptions to the routine mediocrity, meanwhile, are held up to dispel suggestions that the priorities and proclivities of most reporters are so at odds with the duties of a Fourth Estate that their modern role might more accurately be rendered as being "4 the state".

Such is the contention of Guardians of Power, a compilation of five years of work by David Edwards and David Cromwell on their Media Lens website. Operating on a shoestring, the two Davids take a scalpel and a selective magnifying glass to the output of mainstream news organisations, deconstructing for their readers the hidden agendas they find embedded therein. Their focus is not the tabloids, or Rupert Murdoch, or any of the other obvious bugbears and sitting targets. Instead, they reserve their contempt for Britain's "least worst" media, lampooning the Guardian and the Independent as pseudo-radicals and the BBC for its lapses in impartiality.

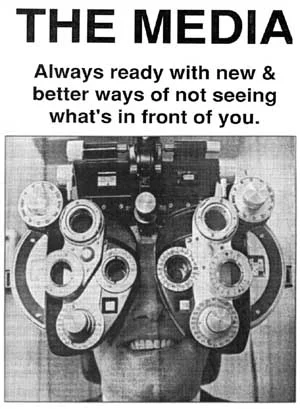

Media Lens, which describes itself as "correcting for the distorted vision of the corporate media", publishes regular newsletters encouraging subscribers to email journalists and challenge their version of events with evidence that contradicts it. The resulting exchanges often reveal parallel universes of incomprehension, but are all the more enlightening because of it. "I'm afraid I think it is just pernicious and anti-journalistic," scoffed the BBC's Andrew Marr in response to a suggestion he was regurgitating government propaganda. A subsequent Media Lens mailout skewered the point home, quoting Marr's Downing Street speech to the nation on the day American soldiers stormed into Baghdad and staged the toppling of a statue of Saddam Hussein. Apparently, or so we were told, this vindicated Tony Blair's support for the invasion. "It would be entirely ungracious," Marr declared on the Ten O'Clock News, "even for his critics, not to acknowledge that tonight he stands as a larger man and a stronger prime minister." Was this what the BBC's premier political reporter described in My Trade, his autobiographical survey of journalistic history, as "the high civic purpose of informing the voters"?

One is reminded of Lord Copper, proprietor of Waugh's fictional daily, The Beast, expounding on his requirements for reporting conflict in colonial Africa:

"Remember that the Patriots are in the right and are going to win. The Beast stands by them foursquare. But they must win quickly. The British public has no interest in a war which drags on indecisively. A few sharp victories, some conspicuous acts of personal bravery on the Patriot side and a colourful entry into the capital. That is the Beast policy for the war."

The arguments about bias in coverage of the Iraq invasion are well rehearsed, but it bears repeating that the BBC, supposedly the bastion of balance, gave less airtime to anti-war opinion than any other British broadcaster. There is no particular conspiracy at work here; it's the logical outcome of an editorial paradigm that regards official sources as the font of all the most newsworthy knowledge. The condition may particularly afflict the BBC, christened "the child of the British parliament" by Marr, but its commercial rivals are by no means immune. "It was my job to report what those in power were doing or thinking," reflects Nick Robinson, who succeeded Marr as political editor after performing the same function for ITN. "That is all someone in my sort of job can do. We are not investigative reporters."

The trouble is that all too few journalists are. "Breaking original stories is expensive and time-consuming," argues Peter Barron, the editor of the BBC's flagship current affairs bulletin, Newsnight. "These days it tends to be the specialists and the bloggers and to some extent print journalists who have the time to really dig away." They tend to have to do so on their own time, however; according to the New Statesman editor John Kampfner, "few news organisations now devote adequate resources to painstaking investigations." Whether or not he counts his own magazine among their number, it has at least sought to document some of the shadows cast over society by big business, to cite John Dewey's definition of politics, such as the influence of nuclear power lobbyists on energy policy. Although Newsnight also unearths scoops of its own, it was striking that one of its most incisive revelations of recent months – an exposé of how foreign companies exploit Iraq's oil wealth – emerged from research conducted by activists on a miniscule budget. "We have to keep the daily beast running," says Newsnight's editor, but it's questionable whether the average day's drip-feed of events and pronouncements is worth the investment of so much attention. After all, as the veteran American broadcaster Bill Moyers observed on his retirement: "News is what people want to keep hidden and everything else is publicity."

Inspired by this dictum, and others of a similar ilk, like the view of Israeli journalist Amira Hass that the reporter's true vocation is "to monitor power and the centres of power", the editors of Media Lens aim to "democratise the setting and content of news agendas, which traditionally reflect establishment interests". Essentially, they're talking about a responsibility to speak truth to power instead of acting as its stenographers. Passion of this kind, widely regarded as the preserve of ideologues, or practitioners of a suspect pursuit dubbed "crusading journalism", has been as unfashionable as fedoras for at least as long. Its reputation is undergoing a prominent rehabilitation, however. Good Night, and Good Luck, George Clooney's film about the chainsmoking CBS correspondent Edward R. Murrow and his showdown with Joe McCarthy, is less about anticommunist witch-hunts than the question of what TV journalism is actually for. The urgency of Murrow's closing monologue, delivered as a speech to broadcasting bigwigs in 1958, is only heightened by the industry's failure to heed it over the intervening half century:

"This instrument can teach, it can illuminate; yes, and it can even inspire. But it can do so only to the extent that humans are determined to use it to those ends. Otherwise it is merely wires and lights in a box. There is a great and perhaps decisive battle to be fought against ignorance, intolerance and indifference. This weapon of television could be useful."

Of course, the BBC – like Channel 4 and even, on occasion, ITV – still has its moments. The odd documentary gem glimmers among the anodyne nuggets hewn from the current affairs coalface; the skeleton of Panorama, to quote one of its longest-serving correspondents, Tom Mangold, "rises occasionally, rattles a chain or two, then sinks back into its coffin". But the business of presenting the stories of the day is entrusted to blow-dried personalities who, as Andrew Marr once boasted of himself, have all had their organs of opinion removed. The consequences for a corporation scared witless by the Hutton report are stark: instead of setting the agenda, its staff, with the exception of a couple of combative interviewers, simply communicate other people's. "Our purpose needs to be to report and enquire on behalf of our audiences," insists Peter Horrocks, the BBC's Head of Television News. "That is different from journalism which has as its purpose the intention of undermining or denigrating authority." Quite how his reporters are supposed to deal with truths that do just that is, like so much else, simply left unsaid.

The hands of newspaper journalists appear at first glance to be relatively untied. Simon Kelner, the editor of the Independent, prides himself on having shrunk his publication to tabloid size while expanding the horizons of its writers by giving them freer rein to speak their minds. "The X-factor which will make people choose your newspaper over another," believes Kelner, "is the way it adds to their understanding of what's going on in the world and gives them a depth of opinion, comment and analysis that other media don't have." Critics may mock his populist "viewspaper" as a Daily Mail for Liberal Democrats, but its front-page banner headlines have at least been screaming about the climactic chaos that may yet wipe out human life on swathes of the earth's surface. When it comes to the question of solutions, however, the Independent is stuck with slogans, ethical shopping guides and exhortations to switch off domestic appliances. Questioning the logic of our addiction to energy-sapping economic growth, on which its own drive for profitability depends, seems as alien to its executives as banning adverts for cars, or the cheap flights that pump so much carbon into the atmosphere. When Media Lens suggested as much, the deputy editor of the Independent on Sunday dismissed readers who emailed him in protest as "a curmudgeonly lot of puritans, miseries, killjoys, Stalinists and glooms."

More insidious, perhaps, than this refusal to lobby for top-to-bottom social change is the subtle way in which stories are framed to present assumptions about the status quo as simple statements of fact. Despite its frequent hand-wringing about the arms trade, the Independent kicked off its recent announcement of a £10 billion fighter jet sale to Saudi Arabia by declaring: "Britain's aerospace industry received a massive boost yesterday." No mention, however, of the massive dent in Whitehall's commitment to human rights when there's a profit to be turned arming one of the world's most repressive regimes, even though the deal was deemed so "likely to heighten tension in the Middle East" that this prospect was highlighted a few sentences later. "It is not important to make sense," stress the Media Lens editors, if one aspires to a successful career in journalism. "It is important only to be able to bandy the jargon of media discourse in a way that suggests in-depth knowledge." This is particularly true of bored jobsworths on the editing desk, who can generally be relied upon to rewrite stories to accord better with received wisdom. Once again, the visions conjured up by the newsroom of Waugh's Beast are by no means as outlandish as they sound:

"On a hundred lines reporters talked at cross purposes; sub-editors busied themselves with their humdrum task of reducing to blank nonsense the sheaves of misinformation which whistling urchins piled before them."

The Guardian, long synonymous with left-liberal opinion, typos and embarrassing corrections and clarifications, is rebranding itself as the antidote to such cavalier practices as front-page editorialising. "This is an upmarket, serious mainstream newspaper," announced its editor, Alan Rusbridger, after spending £80 million on a new midsized format that has already won an award for its au courant colour palette. "There's more potential for growth there than taking comfort in political positioning." Shortly after the paper's relaunch, a leader writer insisted in the face of the latest cataclysm in Iraq that "no one is arguing for an immediate pull-out, and Britain must discharge its responsibilities," whatever they may be. Not only did this assertion ignore countless anti-war activists who've been demanding a withdrawal since Iraq's borders first were penetrated, it overlooked a front-page puff picture of the newest recruit to the Guardian comment pages, the former Times editor Simon Jenkins, resplendent beside the caption: "It's time to leave Iraq."

Translated from the journalese, the Guardian leader was observing that nobody with the power, or the corresponding inclination, to say "cut and run" had any intention of giving such an order. Unless steeped in the skills of Kremlinology, however, a right-thinking reader would be none the wiser. The effect, noted by George Orwell, is one of "words falling upon the facts like soft snow, blurring their outlines and covering up all the details." Elsewhere in the same edition of the paper, senior columnist Jonathan Freedland gave clearer form to the bind in which many journalists find themselves. Castigating Labour MPs for their supine acceptance of Blair's crimes, in terms that applied almost equally to his own comments, Freedland's frustration was palpable. "There is no outrage, just a shrug of the shoulders," he mused on page 31, lamenting further: "there is no realistic way of getting rid of him," without so much as spelling out why the prime minister ought to be held to account, let alone demanding it in plain English.

The intellectual straightjacket hobbling reporters is institutionalised by their definition of who, or what, makes news. Aside from crime stories, disasters and slice-of-life sagas of "human interest", editors have collectively decreed that the journalist's democratic duty is to inform people what those in power are doing, and what they plan to do next. Media outlets consequently see themselves as selective channels for the views of politicians and other powerful figures. "If they learn how to use the prime medium of the age," believes the BBC's Andrew Marr, "people like me will be out of a job." This is highly unlikely, not least because the mediation of the messages by supposedly neutral journalists lends them additional credibility. Balance is nominally supplied by canvassing rival political parties for an opposing view, with the weight given to their words determined largely by their power to influence what happens next.

But what of the shades of popular opinion unrepresented by Britain's three principal parties, which have converged on the same pro-business platform? A recent public inquiry, lavishly entitled Power to the People, concluded after 18 months of research that voters were boycotting elections because: "The main political parties are widely held in contempt. They are seen as offering no real choice to citizens." If parliamentary political debate is increasingly a matter of mudslinging rather than fundamental policy difference, it is hardly surprising that media coverage tends towards a focus on who's up and who's down that might as well be headlined: "PM refutes critics with barnstorming blustery bullshit". Matters of more serious concern, meanwhile, such as evidence of a widening gap between rich and poor, or proposals for a radical restructuring of trade rules, pass almost without comment. Unless a prominent figure in the power hierarchy suggests doing something about a development, it's effectively not news, although it might get written up for the record and buried well down the running order.

An influential school of thought, propagated most eloquently by John Lloyd of the Financial Times, holds that journalists in a parliamentary democracy have no business appointing themselves as a substitute opposition. This argument has some merits if taken to mean that televised slanging matches are as much of a waste of space as the prurient obsession with politicians' sexual peccadilloes and other trivial transgressions. But, given that the government has just drawn up a bill enabling it to make laws without the inconvenience of submitting them to parliament, it seems at best a diversion. Dissent is the basis of democracy; if challenging debate and forensic scrutiny are lacking elsewhere, the media ought to be facilitating both, not just offering a mouthpiece to our masters, whether elected or not. "We report, you decide" is the mantra of Fox News Channel, not of responsible journalism for the 21st century, at least not unless it casts its net wider than the cesspool of corporate lobbying and party lines that is modern mainstream politics. If editors are content merely to ride these waves rather than make some of their own, for what are they being so handsomely remunerated other than running a tight ship? It certainly pays to rock some boats more than others if your business is selling audiences to advertisers, as most media companies do to make money.

"How," ask the editors of Media Lens, "can we believe that greed-driven hierarchies of corporate power can provide honest information to democratic society?" The question is intended rhetorically, but it betrays a penchant for sweeping generalisation that detracts from its underlying point. So eager are Edwards and Cromwell to establish the corporate media's systemic shortcomings that they gloss over wide variations in ownership structure, and even performance. Indeed, the companies they most chastise reported most of the facts on which they base their analyses, sometimes on the front page. This is irrelevant, they argue, citing Noam Chomsky and Edward Herman's defence of the "propaganda model" thesis they outlined two decades ago in Manufacturing Consent, the book which begat Media Lens. "That a careful reader looking for a fact can sometimes find it with diligence and a sceptical eye tells us nothing," Chomsky and Herman stressed, "about whether that fact received the attention and context it deserved, whether it was intelligible to the reader or effectively distorted or suppressed."

The problem, then, is essentially one of context. Media Lens and its subscribers berate journalists for pushing facts through an interpretive framework that obscures their significance; for sacrificing analysis on the altar of novelty; for accumulating information without joining up the dots. Editors tend to favour news stories that recycle the idées fixes of conventional wisdom in their presentation of background material. These are regarded as unbiased, while those structured on alternative interpretations arouse suspicion. Newspapers consequently devote forests of column inches to supposed scepticism, which takes as its starting point the premises of those it purports to challenge. This "feigned dissent", according to Edwards and Cromwell, is the stock-in-trade of liberal commentators, whose heft and vigour belie their conformity to established opinion. More outspoken dissidents, whether opinionated reporters like the Independent's Robert Fisk, or investigative columnists like George Monbiot at the Guardian, survive in pockets, but they don't get to take editorial decisions. As such, the Media Lens editors argue, they may do more harm than good. "Dissident appearances in the mainstream act as a kind of liberal vaccine," they assert, "inoculating against the idea that the media is subject to tight restrictions and control."

This is an absurd claim, predicated on the assumption that there could, even in theory, be any such thing as a truly free press. The repeated references to this holy grail suggest, however, that it is necessarily elusive, serving as a kind of Trotskyist transitional demand with a Situationist twist. "Be realistic, demand the impossible," as the sloganeers of 1968 would have it. Or, more bluntly: "No replastering, the structure is rotten", as if it might somehow crumble of its own accord once enough people noticed. Chomsky and Herman's propaganda model identified five filters distorting media coverage: the interests of parent companies, pressure from advertisers, dependence on official sources, flak from the government and other powerful lobbies and an ideological belief in free-market capitalism. Media Lens seeks to raise awareness of these issues by demonstrating that there are limits to what many journalists are prepared to discuss. More honest reporting is impossible, Edwards and Cromwell argue, unless the filters blurring their vision are removed. "We cannot change the mass media," they write, "until we change the culture, which cannot change until we change the mass media." Their objective is to lobby for a revolutionary restructuring of society by highlighting flaws in journalism, which they ascribe to an all-encompassing theory passed off as axiomatic fact. In effect, then, they are manufacturing dissent.

It is questionable whether the unvarnished truth would be any more likely to circulate under different socio-economic conditions. Apart from anything else, what is truth? According to scripture, Pontius Pilate's famous question went unanswered by no less a mortal than the earthly embodiment of omniscience Himself. Two millennia later, the Austrian novelist and playwright Thomas Bernhard offered a more worldly response. "What matters," Bernhard wrote in his autobiography, Gathering Evidence, "is whether we want to lie or to tell the truth and write the truth, even though it never can be the truth and never is the truth." Journalists rarely report what they see with the candour they deploy when discussing it over drinks. Some might argue this is no bad thing; that comment is free, but facts are sacred, as per the maxim of longstanding Guardian proprietor C.P. Scott. Professional standards are all very well, but not if reporters simply hide behind them to churn out whatever they're being fed, presuming that anything goes as long as it's sourced. It doesn't, argues Samuel Freedman, a Columbia Graduate School professor, in his inspirational Letters to a Young Journalist. "Great journalism," Freedman believes, "comes from the curmudgeons, the dissidents, the lonely individualists, who insist on pursuing what fascinates or outrages them and tracking it to the ground."

Bloggers do this in abundance, but their duelling noise machines are as much a reflection of what's wrong with modern journalism as a tentative response. Reams of guff have been spouted about the transformative potential of a world in conversation with itself, yet the impact on news organisations and their output is minimal: established pundits have merely embraced the same format. Blogging encourages the venting of high-octane opinion, replicating and amplifying trends in the mainstream media, where chic misanthropy seems to be all the rage. Legions of aspirant columnists hone style at the expense of substance, spewing elegant bile like wannabe H.L. Menckens with a status fetish worthy of Tom Wolfe, had he written for Heat magazine. Their online rivals may lack the same pizzazz but they tend to specialise in weightier obsessions, like debunking the arguments of more earnest commentators before their words even hit the newsstand. In this sense, at least, debate is being democratised, if only among the cognoscenti who bother to follow it. Most media consumers continue to assume that "all the news that's fit to print," as the New York Times advertises its contents, will show up in the following day's paper.

The trouble with blogging is that it's largely parasitic. A recent Columbia Graduate School study found that just one percent of posts on current affairs featured an interview with someone else and only five percent involved some other original work, such as examining documents. The rest were commenting on stories researched by professional journalists. Although blogs tend to focus more on broader issues neglected by daily news coverage, they rarely uncover fresh information. Instead, their strength is the way they synthesise it, but the insightfulness of the analysis depends on the author's expertise, not their facility with Google or LexisNexis. "The very ease of online reporting makes it seductive and dangerous," Freedman warns. "In both the blogosphere and the ever-expanding field of media criticism, I see a version of reporting that eschews human contact and first-hand observation, two things that have an inconvenient way of complicating or contradicting one's preconceived opinions."

Away from the world of websites like Indymedia, where activists upload their latest exploits, original reporting costs money, which next to no bloggers generate. This is a significant handicap, as the Guardian editor Alan Rusbridger identified when Media Lens challenged him to justify his paper's dependence on advertising for three quarters of its income.

"I'd be interested to know what alternative business model you propose for newspapers which would sustain a large, knowledgeable and experienced staff of writers and editors, here and abroad, in print as well as on the web. Do you prefer no advertising lest journalists are corrupted or influenced in the way you imagine? If so, what cover price do you propose? Or, in the absence of advertising, what other source of revenue would you prefer?"

Edwards and Cromwell not only have no answer, they argue it's unreasonable to expect one. "The highlighting of important issues for discussion is in itself an important and legitimate activity," they write. This is true, but the discussion has to take place some time. In the meantime, they suggest, Media Lens is an embryonic solution <em>per se</em>, but it is difficult to see how if it only reports on reporting, and does so with dogmatic insistence that the corporate media are irredeemably corrupt. If so, surely action would speak louder than critique, since the only pressure that editors can't ignore is competition. "You must be the change you wish to see in the world," as Gandhi put it. At its best, Media Lens does this, hosting rational debates and disseminating marginalised perspectives, backed up by evidence. But, like bloggers, they piggyback on the work that profit-oriented businesses have paid for.

Ironically enough, one of the new media initiatives they tout as exemplary is itself both profit-oriented and dependent on advertising. In South Korea, one of the world's most wired countries, where broadband Internet is the norm, web-based journalism swept a president from power in 2002. Bypassing the conservative Korean press, thousands of ordinary citizens wrote articles for OhmyNews, a collaborative media site, persuading compatriots to elect a reformist rank outsider. There's more to OhmyNews than group blog advocacy though. Its editors provide basic reporting training for contributors, proofread their submissions and vet them for accuracy and adherence to ethical guidelines. Far from putting media professionals out of business, this model takes advantage of their skills and pays both them and their amateur rivals for their work. "If only journalists would understand how to reinvent themselves," laments Jean K. Min, the director of OhmyNews International. "Trained journalists will be in greater demand as an increasing number of 'citizen journalists' start to produce explosive amounts of news themselves."

Information may want to be free, to paraphrase the cyberpunks, but that doesn't mean it wants to be accurate, as Wikipedia users will recognise. Editorial oversight is essential, both to correct factual errors and to codify a focus for reporting. Nevertheless, a paradigm shift is under way in defining what makes news in the United States, where the spoof newscaster Jon Stewart is widely regarded as the most probing interviewer on TV. From next year, Independent World Television will broadcast a nightly news bulletin financed entirely by viewer subscriptions and relayed by cable, satellite and the Internet. "Informed by a commitment to social justice," the advance publicity announces, "IWTnews will focus on news other media ignore or suppress, and on individuals and groups that are transforming the world." This is no fringe activist outfit; its backers include the executive director of Human Rights Watch and the editor of Harper's, one of America's most highbrow magazines. The news agenda is outlined thematically, from war and peace to such outmoded topics as class, labour issues and social policy, and its editors promise to hire staff "for their experience, political acumen and understanding of history." Workaday hacks need not apply.

Despite the proliferation of cheap video technology, Britain has nothing comparable in the pipeline, in part, perhaps, because fewer viewers see the need. "People tend to suppose journalists are where the news is," the BBC's Martin Bell once observed. "This is not so. The news is where journalists are." More than ever, they're confined to barracks, or hunting in packs, taking cues from almost anyone other than the public they're supposed to be serving. Change is afoot, however. A BBC pilot project is allowing communities in the West Midlands to produce their own programmes for local digital channels, although most of what's screened is still shot by professionals. Once people wake up to the potential of broadband distribution, showcased by sites like Google Video and YouTube and the peer-to-peer file-sharing networks, citizen journalism could start to bite back. The prospect alarms Andrew Marr as much as it fascinates him.

"The digital revolution threatens to do for broadcasting what mechanical presses and cheap paper did for print putting it further beyond the practical control of politicians. They have begun to face up to the looming possibility of a broadcasting world which is as diverse, openly biased and aggressive as print journalism; and they are right to be frightened because such a force might finally destroy the remnants of parliamentary democracy."

Whether or not this conclusion is as overblown as it seems, the empowerment of people to hold their rulers to account is surely the essence of spreading democracy. The court of public opinion can't subpoena witnesses or evidence, so it's ultimately no match for select committees or the judiciary. But, used judiciously, it could chip away at the concentrations of power that dictate policy, forcing government to become more open and decentralised.

It has long been said that journalism's defining mission is to comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable. As Samuel Freedman cautions, however, the world does not divide neatly into oppressors and the oppressed. Speaking truth to power shouldn't morph into misrepresenting reality, presumably with the intention of comforting the powerless. "Being adversarial sounds righteous," Freedman notes, "except when it is a mere reflex, just one more way of imposing black-and-white absolutism on a world washed in greys." The cultivation of compassion, offered as a panacea by Media Lens, is a fine source of motivation, but not much of a guide to what the American writer J. Anthony Lukas termed "the stubborn particularity of life". It's tempting to trade in blithe certainties, like a correspondent ad-libbing to camera, but far more revealing to demystify subjects by exploring their complexities, to sketch out the paradoxes and conflicting points of view. Too many stories are reported from the perspective of the chief protagonists and their peers, for whom they're effectively written. Those on the receiving end are lucky if they get more than a soundbite and the customer is generally short-changed.

If people are to be persuaded to buy their news elsewhere, it has to be able to sell itself. Public service media should inform, educate and entertain, as the BBC's founder Lord Reith suggested, but without undue deference to the establishment, of whose pillars Reith wrote in his diary: "They know they can trust us not to be really impartial." The ultimate challenge is to make sense of the world in real time, as the continuous present is known, not years after the fact. "Genuinely objective journalism," according to the esteemed American reporter T.D. Allman, "not only gets the facts straight, it gets the meaning of events right. It is compelling not only today, but stands the test of time. It is validated not only by 'reliable sources' but by the unfolding of history." Producing it is confoundedly difficult.

First, you have to sift disclosure from disinformation, which is far easier said than done. The public domain is awash with historical evidence, but extrapolating from it to hypothesise about the present is a poor substitute for hard facts. In 1945, the U.S. State Department described Middle Eastern oil as "a stupendous source of strategic power, and one of the greatest material prizes in world history". Half a century later, while still chief executive of Halliburton, Dick Cheney argued that crude's strategic significance was unique. "We are not talking about soapflakes or leisurewear here," the Bush administration's éminence grise told the Institute for Petroleum in 1999. "Energy is truly fundamental to the world's economy. The Gulf War was a reflection of that reality." Yet when Tony Blair was asked in 2003 whether oil was a factor in the decision to invade Iraq again, he dismissed the suggestion as "one of the most absurd conspiracy theories ever". Unsurprisingly enough, journalists devoted even less space to examining the plausibility of this statement than they did to critical appraisal of classified, and therefore apparently incontestable, theories about Saddam's weapons of mass non-existence. Sources with sceptical insight into either question were rarely consulted and only the business press has since kept track of the occupation force's losing battle against pipeline saboteurs and recalcitrant tribesmen. Whatever its role in the push for war, Iraqi oil isn't gushing.

Reporters get distracted from their duty to explain by the pressure to deliver exclusives. Nothing sets the blood racing like the prospect of a front-page splash. But trawling for leaks makes you a conduit for someone's vested interest, which it's difficult to expose without turning off the information tap. Wherever you turn there are sources looking to steer you in a particular direction; it's little wonder that official spin gains such traction in the newsroom when its purveyors have the power to shape your assumptions and even your daily schedule. Scoop depicts these processes in caricature, reflecting Waugh's frustration with his short-lived stint as a correspondent for the Daily Mail in Abyssinia, where he went sightseeing while his rivals filed sensational stories that he couldn't match. Nonetheless, his satire has a ring of truth. When a bogus government tip-off dispatches the rest of the hackpack to a place that doesn't exist, Scoop's hapless hero stays behind. As a result, the Beast's William Boot stumbles across the real conflict in fictional Ishmaelia: a struggle to control its gold reserves, in which a Briton named Baldwin has the upper hand, provided he can press home his advantage militarily. "I possess a little influence in political quarters, but it will strain it severely to provoke a war on my account," the mysterious Mr. Baldwin explains as he feeds Boot the story. "Some semblance of popular support, such as your paper can give, would be very valuable." The relaying of this message requires a certain nuance, however, which Baldwin is conveniently on hand to supply.

"PRESS COLLECT URGENT MAN CALLED MISTER BALDWIN HAS BOUGHT COUNTRY, William began. 'No,' said a gentle voice behind him. 'If you would not resent my cooperation, I think I can compose a dispatch more likely to please…'"

For journalists to set their own agenda, they need editorial backing. A news outlet cannot realistically ignore day-to-day developments, but it's debatable whether there's a requirement to duplicate the efforts of agencies like Reuters and the Press Association to assemble a daily digest. Newspapers are already brimming with rewritten wire reports and agency camera crews shoot much of the foreign footage broadcast on TV. If basic facts were simply conveyed with bullet-point concision, reporters could be freed up to tell the stories behind the headlines, to examine processes instead of events and to analyse what's happening and what might be done about it rather than just the dilemmas that policymakers confront. Stripping out the trivial and the ephemeral needn't make for dull content either. If infotainment remains the order of the day, it doesn't have to be dumbed down to be accessible. Perhaps there is even a gap in the market for a more learned culture of explanation and investigation. Whatever the format, journalism needs to raise its game or the public interest will continue to be cheated by the pursuit of corporate profit and the path of least resistance. "Those that love the world serve it in action," as William Butler Yeats proclaimed.

"And should they paint or write still it is action:

The struggle of the fly in marmalade.

The rhetorician would deceive his neighbours,

The sentimentalist himself; while art

Is but a vision of reality.

What portion in the world can the artist have

Who has awakened from the common dream

But dissipation and despair?"

Scrupulously honest reporting is itself an art, offering but a vision of reality that's fleeting, imperfect and dependent for its sharpness not on opinion, quoted or otherwise, but on well-sourced fact. It's more in demand than ever and yet the news business seems to value it less and less. Swimming against the tide is wearing: resist the pressure to conform to lowest-common-denominator expectations and editors mark you down as a prima donna, a troublemaker or worse. As Nietzsche observed, even the strong are weak when confronted by the organised instincts of the herd. Our greatest physical fear may be death, but psychologically we fear nothing as much as rejection and social exclusion. We hypnotise ourselves into faith in absurdities, if only to hang on to our jobs. Need it always be thus? Journalists of the world, unite! You have nothing to lose but your illusions.