What's The Point?

As published in Pushpam (see here for a more detailed version)

What is the purpose of asana?

By Daniel Simpson

Modern yoga seems synonymous with asana, yet very few postures are described in ancient texts. So how does one practice authentically? Try sitting and holding an arm above your head for several decades.

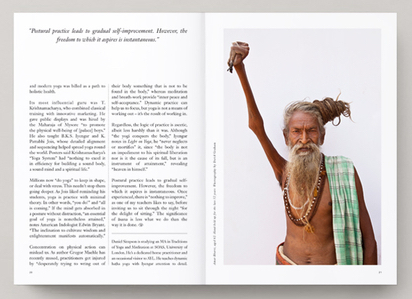

Amar Bharti, photographed in 2010 by David Graham

That's what Amar Bharti does in India. He's an ascetic in Juna Akhara, a traditional group of yogic sadhus. We don't know exactly when yoga began, but early accounts of practice sound like his. More than 2,000 years ago, Alexander the Great's invading Greeks saw naked sages hold contortions. Buddhist sources also talk about austerities, including "meditation without breath", which gave the Buddha "painful, sharp, severe sensations" before he abandoned such extremes. The most hardcore practitioners were Jains, whose self-mortifying goal was to stand or squat until they starved.

These Iron Age ascetics were known collectively as sramanas. Renunciation was their answer to karma and reincarnation, the doctrines of actions and outcomes by which people suffer through endless lives. Focusing on limited activity helped them break the karmic chain, which led to freedom from rebirth. Technically, the term for austerities is tapasya. It derives from tap, which means both "make hot" and "give out heat". This dates back to the Vedas, the oldest surviving Indian texts, in which ritual fire can be internalised. As Indologist Walter Kaelber puts it, "heated effort" yields "liberating knowledge of ultimate reality". Manipulating matter sets the inner spirit free.

The Bhagavad Gita denounced these approaches as "demonic", saying "fierce, heated disciplines" were "thoughtlessly harming the multitude of elements in the body." But as Brahmins asserted control over yogic rebels, they also borrowed their ideas. In late first millennium scriptures, even kings were said to undertake tapasya.

Although ascetics have practised postures for millennia, their physical techniques were first taught in texts 1,000 years ago. Before that, works just listed ways to sit. According to the dictionary, asana is "sitting", or more specifically: "the manner of sitting forming part of the eightfold observances of ascetics". It comes from as, which means "sit quietly", as well as "be present", "make one's abode in" and "do anything without interruption".

Patanjali's Yoga Sutra gives one guideline: sthira-sukham asanam. This doesn't mean postures "should be steady and comfortable"; they get "steadily comfortable" if you're absorbed in meditation. The academic Philipp Maas thus defines the objective as "withdrawing the mind from the perception of the body in order to avoid uncomfortable sensations."

Ascetics speak of practice in these terms. An 18th century man who held both arms above his head said he'd had to be "patient and resigned to the will of the Deity." For a year, "great pain is endured," he told an interviewer, but "the pain diminishes in the third year, after which no kind of uneasiness is felt."

This is the basis of hatha, which translates as "obstinacy" or "force". But as texts on hatha yoga appeared, the concept subtly changed its meaning. By the 15th century, it was said to balance solar (ha) and lunar (tha) energies, raising kundalini up the spine. This Tantric technique for dissolving the mind was grafted onto older practices. Sun and moon meant the right and left nostrils or energetic channels (nadis), as well as the upper and lower breaths (prana and apana), which hatha unites to stoke bodily fires.

Ultimately, the goal was still samadhi: absorption in non-dualistic self-awareness. But asana was essential preparation. The Hatha Yoga Pradipika said postures "give steadiness, health, and lightness of the body" for breath-work and mudras, which clarify nadis for "concentration on nada" (internal sounds).

The inaugural issue of Pushpam magazine

By the 18th century, 100-plus asanas had been taught. To quote research by Jason Birch: "there are very few seated, forward, backward, twisting and arm-balancing poses in modern yoga that have not been anticipated." Yet to Indian elites under British colonisation, postural practice seemed undignified. Their notion of yoga was more intellectual: the rarefied heights of Vedanta or the meditative depth in Patanjali's aphorisms. In the early 20th century, this changed. Interest in exercise helped revive asana. Pioneering teachers began to discuss it in terms of "science", and modern yoga was billed as a path to holistic health.

Its most influential guru was T. Krishnamacharya, who combined classical training with innovative marketing. He gave public displays and was hired by the Maharaja of Mysore "to promote the physical well-being of [palace] boys". He also taught B.K.S. Iyengar and K. Pattabhi Jois, whose detailed alignment and sequencing helped spread yoga round the world. Posters said Krishnamacharya's "Yoga System" had "nothing to excel it in efficiency for building a sound body, a sound mind and a spiritual life".

Millions now "do yoga" to keep in shape, or deal with stress. This needn't stop them going deeper. As Jois liked reminding his students, yoga is practice with minimal theory. In other words: "you do!" and "all is coming". If the mind gets absorbed in a posture without distraction, "an essential goal of yoga is nonetheless attained," notes the scholar Edwin Bryant. "The inclination to cultivate wisdom and enlightenment manifests automatically."

Concentration on physical action can mislead us. As Gregor Maehle, a teacher and author, has recently mused, practitioners get injured by "desperately trying to wring out of their body something that is not to be found in the body," whereas meditation and breath-work provide "inner peace and self-acceptance." Dynamic practice can help us to focus, but yoga is not a means of working out: it's the result of working in.

Regardless, the logic of practice is ascetic, albeit less harshly than it was. Although "the yogi conquers the body," Iyengar observes in Light on Yoga, he "never neglects or mortifies" it, since "the body is not an impediment to his spiritual liberation nor is it the cause of its fall, but is an instrument of attainment," revealing "heaven in himself."

Postural practice leads to gradual self-improvement. However, the freedom to which it aspires is instantaneous. Once experienced, there is "nothing to improve", as one of my teachers likes to say, before inviting us to sit through the night "for the delight of sitting". The significance of asana is less what we do than the way it is done.

--

Pushpam is a quarterly (or so) yoga magazine, published by Hamish Hendry of Astanga Yoga London.

Further Reading

A longer version of this essay (with more details and sources) is published here: