More Mindful Schools?

Published in Contemporary Buddhism, 2017; available here in PDF

FROM ME TO WE: REVOLUTIONISING MINDFULNESS IN SCHOOLS

Daniel Simpson 1

ABSTRACT

The practice of mindfulness adapts Buddhist meditation to everyday life. It seems effective at managing depression and anxiety, and is taught in schools to boost resilience and grades. Mostly, this prioritises calm. Students learn to focus on themselves, without Buddhist teachings on ethics or interdependence. This limits the scope for transformation. Whilst it can help to share techniques to cope with stress, it would be more insightful to target its causes not just symptoms. Instead, a fixation on self gets reinforced, which serves the prevailing market system. The onus is on individuals to be more resilient, instead of changing how things work. Widening inequality and a volatile climate are communal expressions of the roots of suffering, identified by Buddhists as greed, hatred and delusion. If mindfulness in schools were to cultivate "moral and civic virtues", as British members of parliament argue it should, it could foster compassionate "pro-social" action.

INTRODUCTION

Whenever we have in mind the discussion of a new movement in education, it is especially necessary to take the broader, or social, view. - John Dewey (1899)

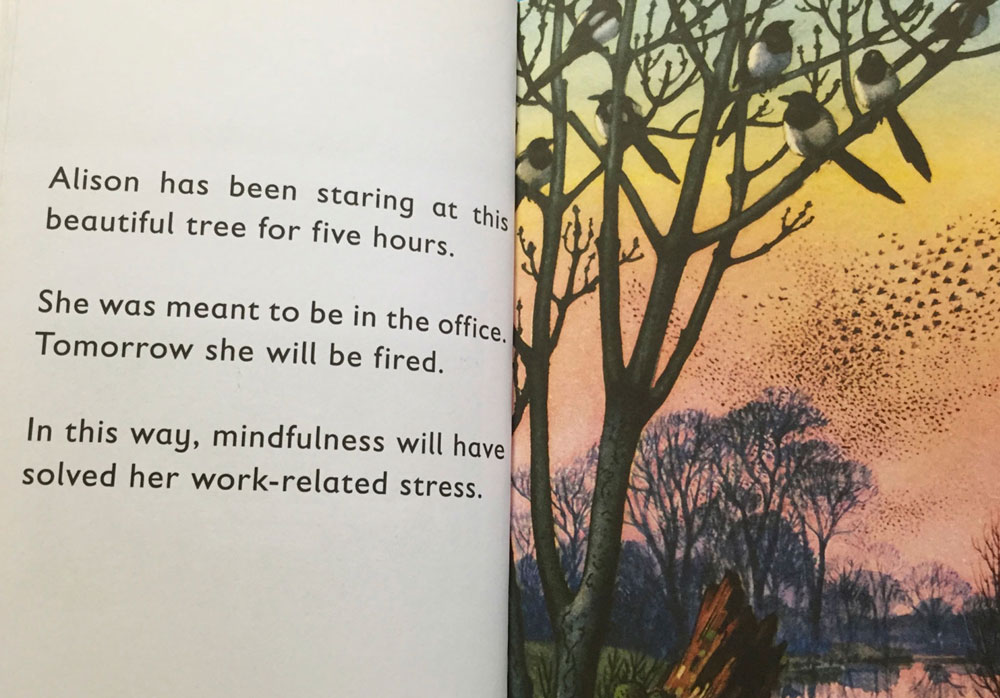

Mindfulness is now such a buzzword that a book making fun of it became a bestseller in 2015. "Mindfulness is the skill of thinking you are doing something when you are doing nothing", it explained, using examples based on pictures from Ladybird children's books. "Alison has been staring at this beautiful tree for five hours", one caption read. "She was meant to be in the office. Tomorrow she will be fired. In this way, mindfulness will have solved her work-related stress".2

A report published one week earlier was more upbeat. Produced by the UK's Mindfulness All-Party Parliamentary Group (MAPPG), it outlined blueprints for "a National Mental Health Service which has, at its heart, a deep understanding of how best to support human flourishing and thereby the prosperity of the country". This boiled down to teaching mindfulness in hospitals, prisons, workplaces and schools, as a way of "addressing some of the most pressing problems of society at their very root – at the level of the human mind and heart".3

Despite acknowledging links between mindfulness and Buddhism, the report was presented in secular terms. It said mindfulness was more than meditation, but rooted in science not belief. A foreword by the prominent teacher Jon Kabat-Zinn called it: "a universal human capacity" that is "best described as 'a way of being'". In practice, it amounts to more than concentration. "Kindness and an inclination towards compassion are essential features", a footnote stressed: "it always inclines towards ethical and pro-social approaches".4

This article examines these claims in the context of schools, which could shape a generation's "way of being". For education, the report lists "three key policy challenges". Two are general priorities: "improving results" and "mental health". The third is specific to the young: a focus on "character-building and resilience", encompassing "a wide range of moral and civic virtues".5

To consider how these might be instilled, I look in detail at the most widely used syllabus in UK classrooms. Designed by the Mindfulness in Schools Project (MiSP), it is currently the subject of a study led by Oxford University, with a view to providing it in many more schools. At present, the course says little about "moral and civic virtues". My aim is to show how a compassionate ethical framework might be included. As identified in parliament, there is otherwise a danger of "a subtle practice" being "presented simplistically, or with misinterpretations".6

Academics also share these concerns. A compelling critique calls the problem "McMindfulness", which means trading on the Buddha's reputation for insight to hawk "a stripped-down, secularized technique" for mass consumption, to quote two Buddhist scholars. The issue with this "Faustian bargain", argue Ron Purser and David Loy, is that it sells people short. "Rather than applying mindfulness as a means to awaken individuals and organizations from the unwholesome roots of greed, ill will and delusion", as the Buddha did by drawing attention to interdependence, "it is usually being refashioned into a banal, therapeutic, self-help technique that can actually reinforce those roots".7

MiSP-trained teachers are urged to be "kind, calm, compassionate and rational", and "a quiet ambassador for the values" of mindfulness. Yet they mainly tell students to focus on themselves. A staff handbook says the course "is about being happy". It also suggests "a deeper sense of peace and wellbeing might come from a sense of purpose", but this is not defined. Relationships with others are only discussed in the penultimate class, when "showing your gratitude" is pitched as "actually really good for you".8

Studies show mindfulness teaching in schools improves behaviour, mood and social skills in students, though how this works remains unclear due to flawed research methods.9 That there are benefits seems beyond doubt. But to what extent are they "pro-social", beyond hoping inner peace will somehow fuel communal harmony?

Mindfulness evangelists imply the world will change if we pay more attention to ourselves. This serves a system reliant on hyper-individualism, and could exacerbate the narcissism inflamed by social media. Students learn self-pacifying skills, but not to question the sources of stress in societies ruled by corporate values. They risk getting trained to be functional cogs in a brutal machine, when they could be empowered to change its workings.

The following pages chart this process. I begin by examining mindfulness in Buddhism, to which virtuous conduct is integral. Next, I explore therapeutic meditation, which prioritises calm without guidance on ethics or interconnection. After surveying teaching in schools, I conclude both are needed, and look at ways to make practice "pro-social".

A more communal view of mindfulness is urgent. Human-induced change in the climate could make swathes of the planet uninhabitable, while our fixation on economic growth sustains resource wars, widening gaps between rich and poor. Radical change involves "going to the root", says the Oxford English Dictionary, "touching upon or affecting what is essential and fundamental". The Buddha tackled causes of problems, not their symptoms. Secular teaching could too, if framed accordingly.

WHAT IS MINDFULNESS?

Mindfulness has multiple meanings, in modern usage and in ancient Buddhist texts. For roughly a century, it has been the most common translation of sati, a word in Pali from the Buddha's collected teachings. Yet the Pali Text Society's dictionary lists sati as: "memory, recognition, consciousness", with "mindfulness" a secondary definition.

Early translators were possibly mindful of Christian parallels. For example, the King James Bible uses "mindful" for the Latin memor in Psalms 8:4: "What is man, that thou art mindful of him?" Buddhist scholars have also used "mindfulness" for different Pali terms (such as appamada, or vigilance), and related English words for sati, which in meditative contexts suggests – among other things – being attentive.

Contemporary therapies are based on the findings of Jon Kabat-Zinn, a bio-medical scientist who taught meditation to patients in pain. Mindfulness helps reduce stress, concludes Kabat-Zinn, by a process of "paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally", which "nurtures greater awareness, clarity, and acceptance" of how things are.10

Buddhist goals are more ambitious, pursuing awakening and compassionate action not endurance. As the Buddha reportedly put it in one of his discourses: "the four ways of establishing mindfulness" are "a path leading directly to the purification of beings – to passing beyond sorrow and grief, to the disappearance of pain and discontent, to finding the proper way, to the direct experience of nibbana".

Enlightenment is not an advertised product of self-help mindfulness.

BUDDHIST THEORY

Traditional texts say effort is required for the "setting-up of mindfulness", the original translation of Satipatthana in two early discourses.11 Their descriptions are not as succinct as Kabat-Zinn's, or solely focused on the present. They offer guidance on how to observe one's inner world, which entails making judgements to avoid unwholesome states of mind. Although mastering the Buddha's teachings might take lifetimes, warns the Satipatthana Sutta, skilful practice can yield liberation in one week.12

Mindfulness is said to be established in four ways: "watching the body as body", then "feelings as feelings", the "mind as mind" and conceptual "qualities as qualities". A meditator has to be "determined, fully aware, mindful, overcoming his longing for and discontent with the world". The first focus is breath. "Just mindful, he breathes", the Buddha says of a monk. "As he breathes in a long breath, he knows he is breathing in a long breath; as he breathes out a long breath, he knows he is breathing out a long breath". Shallow or deep, he inhales and exhales, "experiencing the whole body" while "watching the way things arise and pass", so "his mindfulness that there is body" becomes "knowledge and recollection in full degree".

The same awareness is brought to activities, and the body's constituent elements and impurities. Feelings are also observed to "arise and pass", then states of mind and abstract concepts, from five hindrances (desire, hostility, lethargy, angst and doubt) to seven components of awakening (mindfulness, discernment, energy, joy, tranquillity, concentration and equanimity). A separate discourse on mindful breathing repeats these guidelines, stressing positive qualities need to be "developed and cultivated".13

If mindfulness is properly established, the Buddha explains, four "noble truths" become apparent. As the Satipatthana Sutta says, a practitioner "truly understands what suffering is, he truly understands what the arising of suffering is, he truly understands what the cessation of suffering is, he truly understands what the practice leading to the cessation of suffering is". More simply put, he gets enlightened.

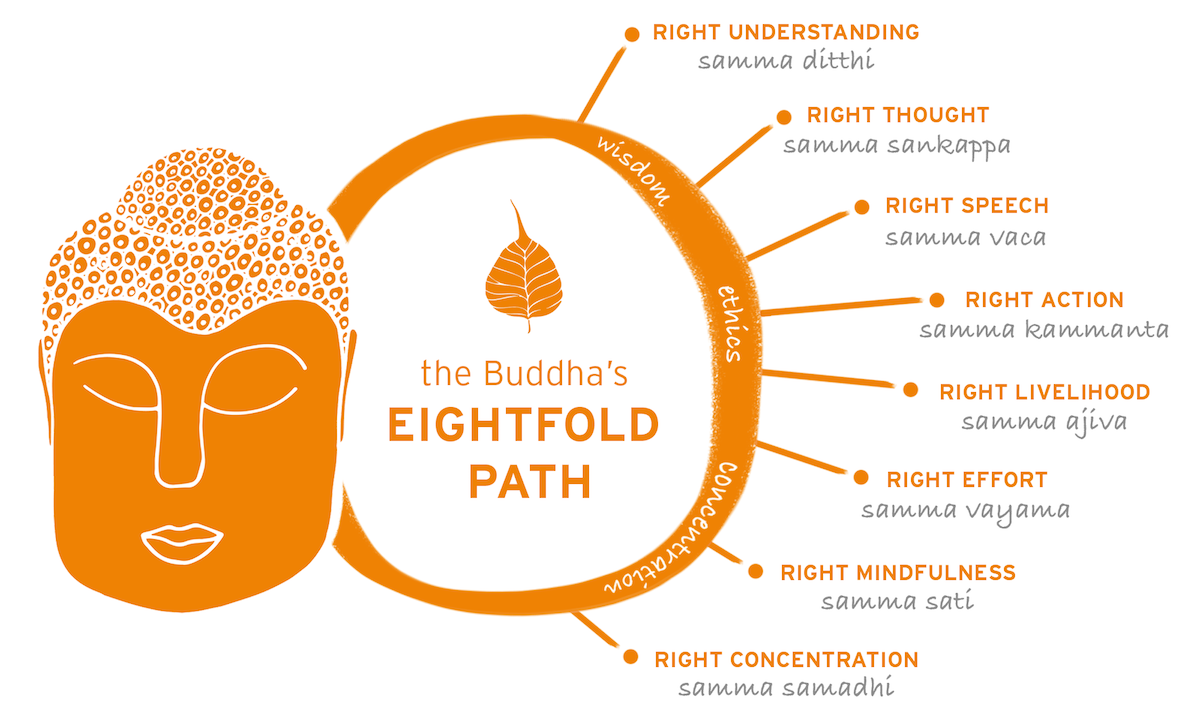

The fourth noble truth, which sets him free, is the eightfold path, the seventh of whose factors is right mindfulness (samma-sati). The first step is right view (samma ditthi), which entails understanding the noble truths, which arise from mindfulness. The path is therefore non-linear and all of its aspects are connected. The others are intention (samkappa), speech (vaca), action (kammanta), livelihood (ajiva), effort (vayama) and concentration (samadhi). Combined, they amount to training in three disciplines: ethical behaviour, meditative practice and liberating insight (in Pali, sila, samadhi and panna). And since each of the steps can be "wrong" (miccha) as well as "right" (samma), they all need work. In Buddhist practice, observes Rupert Gethin: "the eight dimensions are gradually and collectively transformed, until they are established as 'right'".14

Effective meditation combines right mindfulness with right effort and right concentration. Each should be "grounded in the three ethical factors of right speech, right action and right livelihood", explains the American monk and scholar Bhikkhu Bodhi. They are also shaped by the elements of wisdom, Bodhi adds: right view, "which links the practice to understanding", and right intention: "the aspiration for dispassion, benevolence and harmlessness".15

Meanwhile, mindfulness works in conjunction with "clear comprehension" (sampajanna).16 The two concepts are so closely linked that the English-Pali dictionary defines mindfulness as sati-sampajanna. This is where memory comes in. The original translator of mindfulness, T.W. Rhys Davids, said sati also meant "recollection" of "certain specified facts" that pertain to insight. "Of these the most important was the impermanence", he wrote, "of all phenomena, bodily and mental", and "the repeated application of this awareness to each experience of life, from the ethical point of view".17

Contemplation shows everything changes, beyond our control and interlinked. The Buddha highlights three core characteristics of existence: impermanence (anicca), suffering (dukkha) and "not-self" (anatta). Put simply, a self-centred worldview causes suffering: trying to satisfy a transient self with ephemeral things fuels disappointment. Mindfulness might help reveal this, but it takes comprehension to turn the insight into wisdom. Nonetheless, emphasises Bodhi, "the whole evolving course of practice leading to enlightenment begins with mindfulness, which remains throughout as the regulating power ensuring that the mind is clear, cognizant, and balanced".18

This applies to both main forms of meditation: calm concentration (samatha), and discriminating insight (vipassana). The insight approach, described above, refines discernment by mindfully observing subtle objects. The other slowly stills the mind, quelling mental activity through four stages of jhana: processes of thinking (vitakka), inquiry (vicara), joy (piti) and pleasure (sukha) give way to one-pointedness (ekaggata). The Buddha mentions both techniques, and commentaries promote them together and individually. As Bodhi says: "Mindfulness facilitates the achievement of both serenity and insight. It can lead to either deep concentration or wisdom, depending on the mode in which it is applied".19

Until recently, few Buddhists meditated.20 A minority of monks aside, most practised differently. Human life was just one potential state of being. How one behaved determined good or bad fortune, spanning lifetimes. Actions led to future incarnations, from deities to hell-realm ghouls, via earthly creatures of all kinds. Practice involved seeking merit to attain better outcomes. People made offerings to monks and a semi-deified Buddha. They were urged to perform good deeds, and to cultivate wholesome states of mind. Whether or not one meditates, these are intrinsic to right view, which shapes right effort and right mindfulness.

The Buddha defined ethical action through prohibitions. He said not to kill, steal, misbehave sexually, tell lies, speak slanderously or harshly, gossip, covet, hate or misinterpret his teachings. Texts also list 10 "perfections". In Mahayana Buddhism, which spread from India to China, Tibet, Japan and beyond, these are: generosity, good conduct, patience, vigour, meditation, wisdom, skilful means, resolution, strength and knowledge. Theravada Buddhists, mainly found in Sri Lanka and South-East Asia, cite different virtues: renunciation and honesty replace meditation and skilful means, while strength and knowledge become loving-kindness and equanimity. The last two are also praised in other contexts, together with compassion and empathetic joy, which form the four "divine abodes" (brahmavihara).

The Buddha's insight extends beyond lists. Upon awakening, he said what he had realised was: "profound, hard to see, hard to understand, peaceful, excellent, beyond mere thought, subtle, to be experienced by the wise".21 What he taught was a "course of training" to be practised; those "beyond training" were enlightened.22

Mahayana teachings include an additional spur to virtue: the Bodhisattva vow. Since nirvana meant ending rebirth, one could defer it and help other beings awaken first. The impulse to do so is said to arise from "Awakening Mind" (bodhicitta), which requires cultivation. Theravada Buddhists draw related ideas from early mentions of altruism in the Buddha's discourses, such as: "The person practicing both for his own welfare and for the welfare of others is the foremost".23 As summarised by Gethin: "we are almost inevitably primarily motivated by the wish to rid ourselves of our own individual suffering". Yet once we are aware that the whole world suffers, we can be "moved by compassion and the desire to help others".24

CONTEMPORARY PRACTICE

Modern mindfulness is often presented as the Buddha's psychological insight, minus Buddhist philosophical baggage that might sound religious. Much of it stems from the writings of Jon Kabat-Zinn.

Like his teachers at the Insight Meditation Society in Massachusetts (Joseph Goldstein, Sharon Salzberg and Jack Kornfield), Kabat-Zinn was brought up in the Jewish tradition. As a student, he stumbled on Buddhism, which gave him ideas. In 1979, he started a "Stress Reduction and Relaxation Program" at medical school, helping patients come to terms with chronic pain. He saw this as a way to share "universal dharma", which "can be understood primarily as signifying both the teachings of the Buddha and the lawfulness of things in relationship to suffering and the nature of the mind".25

Being a scientist, he published research about what worked. This evolved into a course now run worldwide in eight-week programmes. In the 1980s, he began giving talks at other clinics. When referring to Buddhist ideas, he made connections with psychology, calling his method Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR).26 Promoting it, recalls Kabat-Zinn, involved "finding simple and matter-of-fact ways to articulate for professional and lay audiences the origins and essence of those teachings", namely:

– how the Buddha himself was not a Buddhist, how the word "Buddha" means one who has awakened, and how mindfulness, often spoken of as "the heart of Buddhist meditation", has little or nothing to do with Buddhism per se, and everything to do with wakefulness, compassion and wisdom.

Reflecting on his work as "skilful means" to reach an audience, Kabat-Zinn continues: "The intention and approach behind MBSR were never meant to exploit, fragment, or decontextualize the dharma, but rather to recontextualize it within the frameworks of science [...] so that it would be maximally useful". As a result, he says, his magnum opus (Full Catastrophe Living) serves as "a placeholder for the entire dharma".27

Although he no longer calls himself Buddhist, Kabat-Zinn insists: "we can be in touch with the essence of Dharma without diluting it at all, but in some way we have to help each other to do that and to stay honest".28 He expresses the essence of MBSR as "bare attending to sensation in the body", which means observing it without trying to change things, or getting caught up in repetitive thoughts about one's feelings.29

The notion of "bare attention" is contested. Although we can turn down the volume on thoughts, our individual and social conditioning remain as background noise. "Sense experience never operates in an unmediated fashion", explains the Buddhist academic Richard Cohen. "What seems to be direct perception of worldly objects is, in fact, always already an amalgam of sense impressions and intellection".30

Bare attention appeared in English 60 years ago, in The Heart of Buddhist Meditation, by a German monk called Nyanaponika. It now features a blurb by Kabat-Zinn ("The book that started it all"). In Nyanaponika's words: "mindfulness is kept to a bare registering of the facts observed, without reacting to them by deed, speech or by mental comment". However, if "comments arise in one's mind, they themselves are made objects of Bare Attention, and are neither repudiated nor pursued, but are dismissed, after a brief mental note has been made".31

This account seems to mix up the Pali words for mindfulness and attention (respectively, sati and manasikara), which can both be Germanised as Achtsamkeit.32 In other Buddhist texts, says Alan Wallace, attention "refers to the initial split seconds of the bare cognizing of an object, before one begins to recognize, identify, and conceptualize".33 It is thus a preliminary stage to mindfulness. It should only be used as a synonym, argues Bodhi, if "it helps a novice meditator who has newly embarked on this unfamiliar enterprise get a grip on the appropriate way to observe".34

Well-known teachers use the concepts interchangeably. Joseph Goldstein, who taught Kabat-Zinn, turns them upside down, saying mindfulness is "responsible for the development of bare attention", while the latter is the "one quality of mind which is the basis and foundation of spiritual discovery".35

Back to basics was also the theme of What the Buddha Taught, a popular text with early Western Buddhists. Its author said mindfulness was fun: "One who lives in the present moment lives the real life, and he is happiest".36 Savouring the ordinary was part of The Miracle of Mindfulness, by another influential teacher, Thich Nhat Hanh, for whom washing the dishes was meditation. Hanh suggested beginners try: "recognition without judgment. Feelings, whether of compassion or irritation, should be welcomed, recognized, and treated on an absolutely equal basis".37

This echoes Nyanaponika's reference to "noting", which he learned from a Burmese monk, Mahasi Sayadaw, who encouraged meditation outside monasteries. Under British colonial rule, Burmese Buddhists mined arcane texts to write lay handbooks.38 Among the most prolific was Ledi Sayadaw, whose lineage reached Western seekers via S.N. Goenka; a businessman who had found that meditation cured his migraines. Like his teachers, he called the method Vipassana (from the Pali for insight), presenting it as the epitome of mindfulness (although modern mindfulness is often more calming than insightful). He made Vipassana a globalised brand. Its values were non-sectarian, and Goenka emphasised technique. He was Goldstein's teacher.

It was on a retreat at Goldstein's centre that Kabat-Zinn had the vision that created MBSR. What inspired him was a twentieth-century innovation. A few decades earlier, "few everyday Buddhists would have even heard of mindfulness practice", notes the historian Jeff Wilson.39 Today, it is a multi-billion dollar business, in which non-Buddhists manage "middle-class concerns around self-image, health, relationships, work and children", without a hint of nirvana.40

In 2009, Americans spent $4.2 billion on mindfulness therapies, reports the Associated Press. A few years later, the "Search Inside Yourself Leadership Institute" (SIYLI) was spun off from Google. To quote its co-founder Chade-Meng Tan, whose Google job title was Jolly Good Fellow: "The way to create the conditions for world peace is to create a mindfulness-based emotional intelligence curriculum, perfect it within Google, and then give it away".41 SIYLI teacher training costs $10,000, and its website suggests graduates sell courses for $15,000.

Irony seems at the heart of modern therapeutic applications. Buddhists seek to end "attachment to what is understood to be the inherently painful illusion of personal self", says C.W. Huntington, a scholar of religion, "whereas psychotherapy aims to strengthen this same personal self and help make it fully functional".42

The approaches may well be at odds, but combinations help patients. A modification of MBSR seems as effective at managing depression as pharmaceuticals.43 Known as Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT), it channels a simple realisation by its creators: "there was no need to change the content of people's thoughts, but only how they related to this content".44 Bodily sensations, emotions and thoughts get tangled up, so trying to escape from disturbing feelings rarely works. MBCT promotes "friendly awareness", compassionately "welcoming and allowing" whatever arises. People are guided to pay more attention to their bodies. Getting out of their minds can help them break reactive habits, from addictions to depressive rumination.

Much of the mindfulness teaching in schools draws on MBCT.

MINDFULNESS IN SCHOOLS

The Mindfulness in Schools Project grew out of a conference on student well-being in 2007. Two teachers from private schools, Chris Cullen (then at Hampton in London) and Richard Burnett (based at Tonbridge in Kent), met in a queue to see a Cambridge professor about research plans. Both men meditated, and had taught mindfulness as part of religious studies classes. Together with a colleague, Chris O'Neill, who was studying MBCT at Oxford, they drew up a syllabus known as "dot-b" (written ".b"), which stands for "Stop, Breathe and Be!"

A prototype was pronounced "well-accepted" by Felicia Huppert, the Cambridge academic, with pupils showing "improvement in their well-being related to how much they have practiced".45 The course has since become mandatory for Year 10 pupils (aged 14 and 15) at Hampton and Tonbridge. Meanwhile, MiSP has trained almost 3000 staff at other schools to teach dot-b, or an under-11 version called "Paws b" (i.e. "Pause, Be"). Dot-b has been translated and adapted for use in a dozen countries.

Many courses teach young people mindfulness in the UK. Some schools offer meditation, others a Buddhist-based curriculum (for example, Dharma Primary School in Brighton). Groups outside the classroom include Youth Mindfulness and Healthy Minds. No programme has been as widely adopted as dot-b. Recent research in 12 UK schools echoed Huppert's findings, saying practice "may confer resilience at times of greatest stress" by developing "skills to work with mental states, everyday life and stressors".46 Dot-b is being studied by the Oxford Mindfulness Centre, as part of a seven-year project called MYRIAD, which is running a randomised controlled trial on 5700 pupils. MYRIAD will look at how the brain deals with feelings and thoughts, to determine if mindfulness fosters resilience. It is also considering ways of training teachers, and whether speeding this up would lower standards.

Dot-b is presented to teachers as neither "Buddhism by the back door" nor "hippy dippy" relaxation. It builds on a "solid evidence base for teaching mindfulness which comes from careful evaluations of interventions" and the "findings of neuroscience".47 As described to schools by the MiSP trustee Amanda Bailey, it sounds like a hybrid of ancient and modern: "Mindfulness stems from Buddhist philosophy, with its roots in psychology, as a way of understanding and relieving the causes of human suffering".48

In practice, the focus is narrower than this implies.

FRAMES OF REFERENCE

According to dot-b's co-author Chris Cullen,49 the curriculum is "a radical adaptation of MBCT". It seeks "to draw on the precision of understanding of the mechanisms of stress and de-stress that are so clearly articulated in the MBCT manual", but "to take it out of a clinical context" of treating depression. "Just as MBCT has as its main aim to reduce cognitive reactivity", Cullen says, dot-b's intention is to "promote the capacity to respond, rather than react".

Responding involves tuning out of habitual thoughts, which begins with observing them. Meditation reveals how the mind likes to do its own thing. Instead of focusing on breathing, or anything else, it wanders off. The practice is to notice this, and gently bring it back. "There's an attentional muscle that can be trained", explains Mark Williams, an Oxford psychologist who co-created MBCT. He likens it to "single-tasking", anchoring the mind "so we're not just blown by the wind".50

Otherwise, what he calls "narrative preoccupation" can take over. Swamped by uncomfortable thoughts, the mind's dominant "doing mode" seeks solutions. Identifying "feeling bad", it sets a goal of "being happier". The gap between them gets harder to bridge as thoughts spin round. MBSR detaches physical pain from mental habits that compound it. MBCT applies the same techniques to states of mind. The "doing" mode switches to "being" and difficult moods become more bearable. Essentially, Williams says, we are "befriending ourselves", turning self-criticism into self-care.

Dot-b brings this to life in playful terms. "Attention is like a puppy", says the syllabus script, which teachers are encouraged to read until they find their own words. "It doesn't stay where you want it to", but "it brings back things you didn't ask for" and "makes messes". Hence, "in training our minds we have to use the same qualities of FIRM, PATIENT, KIND REPETITION that are needed in order to train a puppy".

In schools, this starts with "mindfulness of hands". Pupils clap then observe tingling palms. Sensations draw attention to the body, as in most of the practices in dot-b. The "core skill" is to "change mental gear, and wake up to exactly what's going on". This is conveyed via a four-step drill that gives the course its title. To "do a .b" means: "STOP whatever you're doing", then "FEEL YOUR FEET on the ground" and the "SENSATION OF BREATHING as it moves", until you find yourself "relaxing into the present moment, BEING HERE NOW!"

The other techniques are as quirkily named, and do similar things. A "FOFBOC" ("Feet on Floor; Bum on Chair") is "a seated body scan", grounding attention while observing sensations, including those of breath, with "patient, kind curiosity". The "7/11" is a standing equivalent, rooting awareness in the feet before counting to seven while breathing in, and exhaling for a count of eleven. "Beditation" is "a FOFBOC that involves scanning through the whole body when we're lying down". And to "sit like a statue" means chair "beditation" for 15 minutes. There is also a "mindful mouthful" (attentive eating), "slowing and savouring" a routine activity, like brushing one's teeth, counting breaths for a minute, and a few group exercises.

Practices are generally framed as in MBCT, which combines MBSR and aspects of cognitive behavioural therapy. Until recently, meditation in schools was primarily training in relaxation, without dot-b's promise to "use our mind to change our brain to change our mind". Books on the subject had subtitles such as: "The Art of Concentration and Centering", and "A Practical Guide to Calmer Classrooms".51

Much of the innovation in schools, both with mindfulness and earlier techniques, has been in the United States. Current programmes there range from the actor Goldie Hawn's MindUP to Wake Up Schools, inspired by Thich Nhat Hanh. Others include Mindful Schools and Inner Explorer. One of the first schemes taught Transcendental Meditation (TM), promoted by the Beatles' one-time guru Maharishi Mahesh Yogi. It was stymied by a lawsuit in the 1970s. A court ruled it "religious",52 although the effect of reciting its mantras is relaxation.53 TM continues in state-run schools with private funding. Since 2005, a programme called Quiet Time has been backed by the film-maker David Lynch's Foundation for Consciousness-Based Education and World Peace, which supports TM teaching on five continents.

Debates endure about whether meditation is religious. Arguing against its inclusion in public schools, the American professor Candy Gunther Brown shrewdly observes: "The fact that there exist secular benefits to mindfulness does not make the practice secular".54 Although proponents, led by Kabat-Zinn, contend the opposite, they undermine themselves, she says, when they "declare that mindfulness embodies the essence of buddhadharma – a case of wanting to have one's cake and eat it too". As Wilson adds: "The simple fact that the assertion that mindfulness is secular must be repeated constantly demonstrates its ongoing entanglement with religion".55

Dot-b is pitched to staff as "unreservedly secular", to be taught "without any reference to Buddhism". In the view of the MiSP co-founder Richard Burnett: "a classroom is not the place for religious instruction".56 However, he aspires to communicate more than pop psychology, positioning dot-b in "the as yet undefined middle-ground between mindfulness as clinical application and mindfulness as spiritual practice".

To shape it, the course needs "scaffolding", Burnett says, borrowing jargon for framework from Kabat-Zinn.57 What form this takes remains unclear. "One thing the scaffolding almost certainly shouldn't be is a 'Buddhist' one", Burnett insists, though he is far less prescriptive about what it should be. He aims to evoke "a sense of possibility", casting mindfulness as "a discipline which can be applied and interpreted in many different ways, whilst leaving it to the pupils to discover which, if any, is most relevant to them".58

Ultimately, dot-b defines itself, through individual points of view.

CLASSROOM FOCUS

Dot-b's mantra for students is: "be in your own bubble". A workbook suggests coming to class "as if you're entering a mind-lab". Instead of feeling obliged to sit still and shut up, pupils are advised to "choose strong silence", which is "when you're quiet because you want to be... because you understand that it will benefit you". The only mention of anyone else is a request "to give space to others" in discussions, so they "feel safe that they can say what they like, without fear of banter or laughter flying back at them".

For teachers, wresting attention away from smartphones, adolescent hormones and other distractions is a challenge. As Burnett stresses, getting through each lesson "depends as much on your experience in classroom management and rapport with your sets as it does on your understanding of mindfulness".59

Staff are reminded "it's all about pace", so "students need to be kept busy, occupied and motivated". If some get unruly, the recommended practice is telling them "to stamp their feet together in time, getting softer and softer until they are quiet". When drowsy, another option is "getting them out of their seats for a mindful stretch".

Given the constraints, including time (dot-b's 10 lessons last barely seven hours, while adult programmes run for 20, plus a practice day), the course is aimed at student needs. Research suggests many use mindfulness for coping with stress, whether due to exams or other pressures.60 Anxiety, depression and behavioural disorders are rife. Officials say a third of adolescents in England have mental health issues, which often recur in adult life.61 This accounts in part for using MBCT techniques, and what Burnett calls: "the central role of 'calm' in motivating pupils".62 Teachers are reminded: "if you can make mindfulness relevant to their lives now, they will often engage with it and use it almost immediately".

The student workbook is down-to-earth, saying: "there is no 'right' or 'wrong' sensation" to observe. The task is to accept "whatever is there, be it comfortable or uncomfortable, familiar or 'weird'". This approach is brought to life by screening a video clip of the naturalist David Attenborough, who sits in the jungle with gorillas. He avoids being mauled by "giving them space to be as they are", quietly and "patiently noticing" but "not interfering". Meditation skills are described as "David Attenborough attitude". To "do a FOFBOC" is to sit "grounded and stable", remaining "open and ready" and "relaxed but alert".

The authors of the syllabus suggest this kindly way of being is compassion; if not for others, at least for oneself, which is where it starts. No instruction is therefore required in such Buddhist ideas as loving-kindness. This assumption derives from the creators of MBCT, who argue: "the very act of gently turning toward and attending to the present moment is a powerful gesture of kindness and self-care".63 They also infer: "seeing kindness in action is the most powerful teaching, whether the instructor is guiding the in-class practices or responding to doubts". More significantly, and contentiously, "moments of mindfulness" are said to "naturally bring with them kindness, compassion, and a sense of balance".

Kabat-Zinn goes even further in this vein. "You don't have to do a lot of propaganda", he says. "The other stuff is completely embedded in the paying attention and the awareness".64 Generalising wildly, he adds: "in all Asian languages the word for mind and the word for heart are the same", so "if one cultivates mindfulness, your heart's gonna change". Eschewing science, he backs this claim with Buddhist theory, saying: "mindfulness is spoken of and described in the texts as a wholesome mental factor". Ergo, "there is an ethical foundation" and "it's not like if you meditate you'll become a better sniper if you're in the military".

Yet this is precisely one of the reasons that soldiers learn mindfulness, without the Buddhist precept not to kill. Buddhists overlook that too, as in militarist Japan in the Second World War, but the rule exists. Mindfulness-based Mind Fitness Training, a U.S. invention, has no equivalent. It builds "a 'mental armor' which both increases warriors' operational effectiveness and enhances their capacity to bounce back from stressful experience".65 It also helps fire guns. Troops "are taught to pay attention to their breath and synchronize the breathing process to the trigger finger's movement, 'squeezing' out the round while exhaling".66 Ethical conduct entails being careful whom one shoots. As the course creator puts it, "an effective warrior needs to be 'monk and killer' simultaneously", showing "self-control during provocation" but being ready "to kill, cleanly, without hesitation and without remorse".67

It seems naive to claim compassion arises naturally. This implies that the mindfulness taught in schools, or in MBSR, is inherently "right", despite lacking the ethical training on which "right mindfulness" depends. Experienced meditators question the logic. Daniel Ingram, a rare Buddhist teacher who calls himself enlightened (his 2008 book, Mastering the Core Teachings of the Buddha, styles him "The Arahat"), says: "if you're doing compassion practices, it's more likely and predictable that compassion will arise".68 However, "a concentrated mind is like a laser beam", he warns. "It can cut something very precisely into a specified shape, or burn someone to death". Ingram cites examples of "people with decades of practice" who "went out of their way to cause other people suffering quite intentionally".

Another Buddhist, Matthieu Ricard, argues persuasively: "there can be mindful snipers and mindful psychopaths who maintain a calm and stable mind. But there cannot be caring snipers and caring psychopaths".69 He thus proposes renaming practice "caring mindfulness" and "embedding a clear component of altruism from the start" to create "a very potent, purely secular way to cultivate benevolence".70

Steps towards this are found in dot-b, in a penultimate lesson called "Taking In The Good". This was added a couple of years ago to introduce gratitude, saying "even the ordinary can be experienced as 'good' if we are more fully aware of it". Students are encouraged to sit, "bringing to mind someone who, at one time or another, has been kind to you", then "seeing if you can soak a little in feelings of goodness and wellness". Homework is to list "three good things" at the end of each day, and "as you breathe out, try just thinking or saying the word 'thank you' as you picture the people or things you are feeling gratitude towards".

The class is reinforced with a video on "The Science of Happiness", produced by a company called SoulPancake. In an onscreen experiment, volunteers name someone who "did something really amazing or important for them". Most are family members, friends and mentors, whom participants telephone to thank. All sound pleased to have done so. The young presenter concludes: "expressing your gratitude will make you a happier person", adding: "Trust me. I'm in a lab coat". Science takes a back seat. One of his interviewees mentions "Jesus Christ, who is responsible for my existence".71 This is somehow OK, although referencing Buddhism is taboo.

The final lesson sums up dot-b as "learning to manage our minds and to live well". This sounds helpful whether pupils are struggling or closer to "flourishing", the watchword of educational well-being. It derives from the Greek eudaimonia, which meant the highest human good, and a primary goal of ancient ethics. Inspired by Martin Seligman, a "positive psychology" professor, schools such as Hampton now supplement mindfulness with classes on potential and "growth mindset". Coined by Carol Dweck, this phrase means: "everyone can change and grow", so "it's impossible to foresee what can be accomplished with years of passion, toil, and training".72

Hampton's "Wellbeing & Resilience Course" includes gratitude and altruism. It explores all aspects of Seligman's theory of how people flourish: by feeling good, being absorbed in activity, finding meaning, nurturing relationships and accomplishing things. Satisfaction, argues Seligman, comes from "belonging to and serving something that you believe is bigger than the self", while "connections to other people and relationships are what give meaning and purpose to life".73 For now, this is not part of mindfulness, either at Hampton or in dot-b.

Chris Cullen says it is "important not to see dot-b as a finished product", since it is "always very much in development". MiSP's Director of Content and Training, Claire Kelly, says plans include "a lesson specifically on the brain and mindfulness, possibly a compassion lesson, one on mindful relationships with social media and technology, and one specifically around exams and anxiety". However, "they're all quite a way off yet".74 The main change in 2016 was new animated films with guided practices, in the hope of enticing more students to use them at home: "the holy grail" in Burnett's words. In 2017, they intend to launch a meditation app.

Mentioning ethics is not a priority. Nor are connections to others, or social causes of obsession with the self. Broadening perspective would help make the syllabus more insightful.

MISSING LINKS

As Burnett explained when devising dot-b, its "working hypothesis" limits its scope. "Whilst in a classroom we can open children's eyes to the possibilities of mindfulness", he wrote, "there is insufficient contact time to expect a radical shift in the way adolescents perceive their world".75 Cullen agreed, saying students would mainly be accessing calm, "with some sense of impermanence and the benefits of not judging". The fundamental insight of interdependence, the Buddha's core teaching,76 was not mentioned.

Leaving this out has significant effects. Dissatisfaction is addressed through symptoms such as stress, not in terms of conditions that create it. And people's focus on themselves seems reinforced, which could strengthen desires and an underlying sense of separation. Dot-b's creators disagree. They quote Kabat-Zinn, who says the calm concentration of mindfulness can be "put in the service of looking deeply into understanding the interconnectedness of a wide range of life experiences", and even "seeing more deeply into cause and effect" so "we are no longer caught in a dream-dictated reality of our own creation".77

However, mindfulness is only a tool. How it works depends on how people use it, and how it is presented. Blithely asserting, like Kabat-Zinn, that mindfulness "implies, or at least invites, seeing the interconnectedness between the seer and the seen" is not the same as teaching insight, even if awareness of "the nature of things" is "available for anybody".78

Some basic guidance would be helpful. Experiencing what Buddhism means by "not-self" can be unsettling. And as the meditation teacher Daniel Ingram warns, "any time you start looking at anything, it's a possibility that you will chance on the realisation" all things are in flux, including us. "It's so glaringly obvious", Ingram says, "it's kind of mind-boggling people don't notice it more often".79

Minds like to cling to illusions. As the Buddha is quoted as saying 2500 years ago: "This generation delights in attachment" and "it is hard for such a generation to see this truth", known as "dependent origination".80 Thich Nhat Hanh sums up its message as: "the egg is in the chicken, and the chicken is in the egg".81 Each needs the other to exist and neither originates independently. Therefore, "a cause must, at the same time, be an effect, and every effect must also be the cause of something else". Hanh labels this concept "interbeing", in which "the one contains the all" and "we are what we perceive". But "we have to see the nature of interbeing to really understand. It takes some training to look at things this way", even if "you only have to dwell deeply in the present moment".82

Just by mindfully drinking tea, Hanh reports, "the seeming distinction between the one who drinks and the tea being drunk evaporates", yielding "a direct and wondrous experience in which the distinction between subject and object no longer exists".83 This message could be part of dot-b, yet when students eat chocolate, they are told simply to "savour the experience". Later, they chew red chilli and are urged to "turn TOWARDS any sensations of discomfort". The point is to notice reactions, and learn to respond less automatically. But a chance to explore "interbeing" goes untaken.

Similarly, dot-b's maxim that "thoughts are not facts" could be expanded. Students learn that we worry because "our minds are addicted to telling stories about what's happening to us" and "many of these stories are fictions". However, nothing is said about what this implies about identity. According to the Thai monk Buddhadasa: "The difference between a worldling and an enlightened person is that the former misconceives 'I' as something real while the latter knows that it is unreal and is used only for conventional purposes".84 Although self-referential thinking helps us function, neuroscience shows it plays roles in mental illnesses. The obsession with "me" causes painful illusions unless we tune out a bit. The philosopher John Dunne calls the process of doing so "non-dual mindfulness", adding: "MBSR is overall adopting a non-dual approach", although rarely overtly.85

Explanations need not be complex or religious (though advanced Mahayana practices are described in non-dual terms). "You are not your mind", declares The Power of Now, a non-dual bestseller:86

Identification with your mind creates an opaque screen of concepts, labels, images, words, judgments, and definitions that blocks all true relationship. [...] It is this screen of thought that creates the illusion of separateness, the illusion that there is you and a totally separate "other." You then forget the essential fact that, underneath the level of physical appearances and separate forms, you are one with all that is. By "forget", I mean that you can no longer feel this oneness as self-evident reality. You may believe it to be true, but you no longer know it to be true. A belief may be comforting. Only through your own experience, however, does it become liberating.

The point is not to venerate the words of Eckhart Tolle, but to argue that insight could be shared through practice in the classroom. Impersonal emptiness is hard to convey in conceptual terms. Telling adolescents they do not exist may not do much to curb their angst. But non-dual awareness could be tasted with sweets.

Reflecting on experiential methods of teaching, David Hay notes: "people who become religiously aware seem to experience directly their solidarity with their fellow human beings and their responsibility towards them". Since "life gains meaning" as a result, Hay says: "these would appear to be advantages of our biological heritage not to be lightly ignored".87 And if they can be accessed in secular terms, why not invoke them to motivate students to act altruistically?

CONNECTING DOTS

With a more holistic view, dot-b could foster social change. Several lessons recycle themes or overlap (for example, 3 and 7; or 1 and 2). At least two classes could be combined, creating space for new material. "Interbeing" suggests a social side to mindfulness. However, if the focus remains on technique, neglecting ethics and insight, students mainly get more mindful of themselves. In some ways, this is ironically disempowering. It reflects the requirements of a competitive market system, which places the emphasis on personal resilience, not on making society less destructive.

UK members of parliament discussed the "radical perspective-shifting potential" of mindfulness. For this to be more than a lofty phrase in their report, schools need to develop the "moral and civic virtues" it alludes to, while disputing its agenda of "improving productivity" and "mental capital".88 The corporate mentality seems so entrenched it gets mistaken for a fact. Yet thoughts are not facts at the social level if we challenge them. Learning to see through illusions is an act of "intellectual self-defense", says the linguistics professor Noam Chomsky, "to lay the basis for more meaningful society".89

Traces of politics may sound as contentious to dot-b's creators as promoting Buddhism, but what is at stake concerns attention. A battle for eyeballs, and the brain cells behind them, rages constantly through electronic media. The performers in this infotainment spectacle range from our friends and celebrity role models, via click-bait journalists and the advertisers paying them, to cabals of corporations and officials. All trade in narratives framed by judgements and opinions, some of which we adopt, very often unconsciously. To quote Kabat-Zinn: "what mindfulness can do for us, and it is a very important function, is reveal our opinions, and all opinions, as opinions".90

Of course, there are limits to what can be taught in a single lesson. But even describing how thoughts are controlled could help sow seeds of civic mindfulness. A class could be based on ideas from The Common Cause Handbook and The Rax Active Citizenship Toolkit.91 Critical thinking gets stronger with practice, like anything else. And as dot-b warns students, "the more we have certain kinds of thoughts and moods without being mindful of them, the easier it is for that particular sort of thought traffic to flow". To be free to develop alternatives, we first have to realise minds get colonised.

"Imagine if the people of the Soviet Union had never heard of communism", muses the journalist George Monbiot, depicting the grip of a "zombie doctrine" on society. "The ideology that dominates our lives has, for most of us, no name" and "its anonymity is both a symptom and cause of its power".92

Knowing its title – neoliberalism – is not much help with making sense of it. Like a glass-and-steel bank headquarters, the term reveals little about what it does. Likewise the slogans behind it, such as Margaret Thatcher's "there is no alternative", an odd-sounding pitch for market choice. Even "free markets" are not what they seem, since they operate with rules. The issue is whom they serve, but "state-backed rackets redistributing wealth to a corporate cartel" has a less catchy ring. Meanwhile, the cult of economic growth, in which much of our "property-owning democracy" (another Thatcher catchphrase) is invested, is destroying the environment that sustains us. Governments seem powerless to stop this. They bail out plutocrats with taxpayer cash, and scale back assistance to everyone else. Inequality widens. If its causes are not widely known, let alone addressed, demagoguery thrives.

Neoliberal logic offers different explanations. We are all consumers, or in the words of the political scientist William Connolly, "regular individuals who have internalized market norms".93 Self-promoting and self-disciplined, we are in charge of our own well-being and success in careers, whatever odds are stacked against us (and to blame if we fail to transcend them, or meet corporate needs). Unless mindfulness is differently framed, it indoctrinates students in neoliberal thinking. As the sceptical professor James Reveley observes: "It is a tall order to ask young people to reject these ideals at the same time as they are being taught to embrace them through a self-technology that stresses self-responsibility".94

Yet reject them we must for the sake of the species. Climactic meltdown is set to engulf us without drastic action.95 Our attachment to the industries causing it continues. Oil, gas, coal, transport and farming all play roles, as do media that fail to inform us how to change. That process starts with solidarity, which neoliberalism purges by attacking trade unions and privatising services, while deregulating business and granting tax cuts to the rich. Companies, which are legally people, avoid billions in tax, yet humans on welfare are typecast as scroungers. Class-consciousness is strong among elites, who help write laws. The rest of us are left feeling marginalised and powerless. Truth seems an undervalued currency.

As the activist Buddhist Bhikkhu Bodhi argues, "climate change, social injustice and glaring economic inequality are moral issues".96 And as "systemic and institutional embodiments" of "the three unwholesome roots: greed, hatred and delusion", they demand mindful action, in the same way as causes of personal suffering. Showing how opinions are used to frame stories, and stifle resistance, might help students view news like thoughts: potentially misleading. "To believe these thoughts", dot-b says, "is to get on board a thought bus and let it take us for a ride". Observing can help us respond with greater skill.

Is social action part of mindfulness? Yes, says Kabat-Zinn, especially "when we are asked so much of the time to accept that black is white" and "as a society we collectively fall time and again into mindlessness, caught up in spasms of madness" such as war.97 Yet he often makes it sound as if the world would transform if we only paid attention to each moment, which would lead to wise choices and influence others. A better guide here might be his father-in-law, the late historian Howard Zinn, who said seismic events depend on "the countless small actions of unknown people that led up to those great moments", so "the tiniest acts of protest in which we engage may become the invisible roots of social change".98

Mindfulness in schools could be a liberating process, opening students to purposeful engagement with the world, and teachers to ways of seeding that in class. Without a social and moral dimension, however, it is merely a way of inducing calm, with the purpose of flourishing individually. Parents at fee-paying schools (where dot-b began) might well be aghast if their offspring stopped trying to pass exams, to amass student debt and seek better-paid jobs. Yet the National Union of Students says half of new graduates return home to their families, and official statistics show a quarter earn below average wages 10 years later.99

The suggestion to students to "do a dot-b" when feeling stressed, instead of questioning the need for endless tests and "self-improvement", is what the education professor David Forbes calls "a disguised pedagogy of social control".100 As such, it sounds a little like soma in Brave New World and the behavioural conditioning that says swallow drugs and just chill out: "Was and will make me ill", a young woman recites. "I take a gramme and only am".101

CONCLUSION

Mindfulness has obvious benefits. It can be useful to watch thoughts and feelings come and go, without getting caught up in reactive habits. It makes sense to teach children this skill, and to highlight ways they might immediately use it in their lives. If this is all they are taught, however, their understanding of mindfulness, and how it might alleviate human suffering, will be limited.

Dot-b would be more insightful if it embraced a social view. This is not only so because Buddhists endorse it (through the ethical and insight components of the eightfold path, and via interdependence), or because positive psychologists posit the same (saying flourishing depends on relationships with others). Kabat-Zinn agrees, writing at length about "Healing the Body Politic",102 and presenting mindfulness to parliamentarians as a technique for "transformation, going beyond the limitations of our presently understood models of who we are as human beings and individual citizens, as communities and societies, as nations, and as a species".103

What transforms us is more than attention, both in Buddhist theory and secular practice. Yet for all the insistence by contemporary teachers that nothing important gets left out of modern mindfulness, they mainly teach ways to pay attention, with little to say about ethics or insight, either conceptually or in action – though Kabat-Zinn claims his version "subsumes all of the other elements of the Eightfold Noble Path, and indeed, of the dharma itself".104 Everything is allegedly embedded in compassionate technique. Therefore, if teachers are properly trained, they automatically share the other parts. That sounds far-fetched if students focus on themselves. It may be true that a mindful glow sometimes radiates out as kind behaviour. But if similar training helps soldiers fire guns, it seems more context might be needed.

Mindfulness can serve unwholesome ends. In schools, it can be used as a tool to mould compliance. For example, Patterson High School in Baltimore has a "Mindful Moment Room", to which "teachers may send distressed or disruptive students for individual assistance with emotional self-regulation". The UK parliamentary report endorsed this aim as well as improving school results, on which managers are judged.105 Neither seems the motivating ethos of dot-b. Nonetheless, it trains students in ways that support an unjust social order. A clearer purpose would be helpful. When devising the syllabus, Burnett asked of mindfulness: "what are its underlying values?" For the classroom, he decided the answer was: "to inspire and enable, without being overly prescriptive".106 He presumably avoids promoting greed, ill will or delusion, so prescribing their opposites seems uncontroversial. Saying mindfulness is non-judgemental is a cop-out. Judgements are involved in deciding what gets taught.

A broader approach would incorporate ethics, developing what Forbes calls "a democratic, civic mindfulness that creates an equitable and shared meaning of the common good".107 Attention could progressively shift from "me" to "we", avoiding narcissistic self-absorption. As in loving-kindness meditation, it is logical to start with oneself and widen out to other people. Unless we feel calmer, it is hard to consider them. Beyond the inter-subjective "we", there is also an inter-objective "its": the realm of systems and of nature. For meaningful transformation, each is as important as "me" (as well as the "it" of assessing effectiveness objectively). To imagine that by healing ourselves we heal the world is to choose the illusion that fooled the hippies of the 1960s. Inner and outer are linked, but both need work.

Future studies could explore specific ways to combine teaching of mindfulness with critical thinking. Pedagogy based on compassion and social justice could examine conditions that shape our behaviour in unwholesome ways. "When compassion and justice are unified", contends Bhikkhu Bodhi, this "gives birth to a fierce determination to uplift others, to tackle the causes of their suffering, and to establish the social, economic, and political conditions that will enable everyone to flourish".108

Dot-b is inevitably a partial introduction. But need it really leave so much out? Could remedies for suffering not be sought in more dimensions, including action informed by an ethical point of view? Mindfulness is one of eight aspects of a process of inquiry. The eightfold path is a system of practice not belief. More of its insights could be secularly framed to raise awareness.

Anyone is free, of course, to take a narrow view. MBSR and MBCT both state quite clearly what they do (reduce stress and provide cognitive therapy). By not calling itself "mindfulness-based", dot-b suggests a broader aspiration. Yet if the bulk of the path is ignored, and its methods are introductory calming meditations, can it really be said to teach mindfulness in schools?

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks to the Mindfulness in Schools Project for sharing course materials; to Chris Cullen and Daniel Ingram for interviews; to Tessa Watt and Ron Purser for reading suggestions; to Zoë Slatoff and Eugene Romaniuk for guidance; and to Matthew Green for inspiration.

ABBREVIATIONS

Citations of canonical texts refer to the editions published by the Pali Text Society. The source of translated quotations is listed below.

AN – Anguttara Nikaya. Quotations trans. Bodhi (2012).

DN – Digha Nikaya. Quotations trans. Walshe (1995).

MN – Majjhima Nikaya. Quotations trans. Ñanamoli and Bodhi (1995) unless stated. Additional quotations trans. Gethin (2008).

SN – Samyutta Nikaya, quotations trans. Bodhi (2000).

REFERENCES

Bailey, Amanda. 2014. "A Focus on Mindfulness." Headteacher Update 2014 (2): 30–31.

Bodhi, Bhikkhu. 1994. The Noble Eightfold Path: The Way to the End of Suffering. 2nd ed. Kandy: Buddhist Publication Society.

Bodhi, Bhikkhu, trans. 2000. The Connected Discourses of the Buddha: A Translation of the Samyutta Nikaya. Boston, MA: Wisdom Publications.

Bodhi, Bhikkhu. 2011. "What Does Mindfulness Really Mean? A Canonical Perspective." Contemporary Buddhism 12 (1): 19–39.

Bodhi, Bhikkhu, trans. 2012. The Numerical Discourses of the Buddha: A Translation of the Anguttara Nikaya. Boston, MA: Wisdom Publications.

Braun, Erik. 2013. The Birth of Insight: Meditation, Modern Buddhism and the Burmese Monk Ledi Sayadaw. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Brown, Candy Gunther. 2016. "Does Mindfulness Belong in Public Schools? No." Tricycle 25 (3): 63–65.

Buddhadasa, Bhikkhu. 2002. Towards Buddha-Dhamma. Translated by Nagasena Bhikkhu. 2nd ed. Surat Thani: Dhammadana Foundation.

Burnett, Richard. 2011. "Mindfulness in Secondary Schools: Learning Lessons from the Adults, Secular and Buddhist." Buddhist Studies Review 28 (1): 79–120.

Chomsky, Noam. 1989. Necessary Illusions: Thought Control in Democratic Societies. London: Pluto Press.

Cohen, Richard. 2006. Beyond Enlightenment: Buddhism, Religion, Modernity. London: Routledge.

Connolly, William. 2013. The Fragility of Things: Self-organizing Processes, Neoliberal Fantasies, and Democratic Activism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Department for Education. 2016. "Graduate Outcomes: Longitudinal Education Outcomes (LEO) Data." DfE, August 4, 2016. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/graduate-outcomes-longitudinal-education-outcomes-leo-data.

Dewey, John. 1899. "The School and Society." Reprinted in John Dewey on Education: Selected Writings, edited by Reginald Archambault, 1974, 295–310. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Dunne, John. 2011. "Toward an Understanding of Non-dual Mindfulness." Contemporary Buddhism 12 (1): 71–88.

Dweck, Carol. 2006. Mindset: The New Psychology of Success. New York: Ballantine.

Eaton, Joshua. 2013. "American Buddhism: Beyond the Search for Inner Peace." Religion Dispatches, February 20. http://religiondispatches.org/american-buddhism-beyond-the-search-for-inner-peace.

Erricker, Clive, and Jane Erricker, eds. 2001. Meditation in Schools: A Practical Guide to Calmer Classrooms. London: Continuum.

Farias, Miguel, and Catherine Wikholm. 2015. The Buddha Pill: Can Meditation Change You? London: Watkins Publishing.

Felver, Joshua, and Patricia Jennings. 2016. "Applications of Mindfulness-based Interventions in School Settings: An Introduction." Mindfulness 7 (1): 1–4.

Felver, Joshua, Cintly Celis-de Hoyos, Katherine Tezanos, and Nirbhay Singh. 2016. "A Systematic Review of Mindfulness-based Interventions for Youth in School Settings." Mindfulness 7 (1): 34–45.

Forbes, David. 2015. "They Want Kids to Be Robots." Salon, November 8. http://www.salon.com/2015/11/08/they_want_kids_to_be_robots_meet_the_new_education_craze_designed_to_distract_you_from_overtesting.

Forbes, David. 2016. "Modes of Mindfulness: Prophetic Critique and Integral Emergence." Mindfulness 7 (6): 1256–1270.

Gates, Barbara, and Alan Senauke. 2014. "An Interview with Jon Kabat-Zinn: The Thousand-year View." Inquiring Mind 30 (2): 14–15, 30.

Gethin, Rupert. 1998. The Foundations of Buddhism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gethin, Rupert, trans. 2008. Sayings of the Buddha: New Translations by Rupert Gethin from the Pali Nikayas. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Goldstein, Joseph. 1976. The Experience of Insight: A Simple and Direct Guide to Buddhist Meditation. Boston, MA: Shambhala.

Hanh, Thich Nhat. 1976. The Miracle of Mindfulness. Boston, MA: Beacon.

Hanh, Thich Nhat. 1999. The Heart of the Buddha's Teaching. London: Rider.

Hay, David. 1987. Exploring Inner Space: Scientists and Religious Experience. 2nd ed. Oxford: Mowbray.

Hazeley, Jason, and Joel Morris. 2015. The Ladybird Book of Mindfulness. London: Michael Joseph.

Holmes, Tim, Elena Blackmore, and Richard Hawkins. 2011. The Common Cause Handbook: A Guide to Values and Frames for Campaigners, Community Organisers, Civil Servants, Fundraisers, Educators, Social Entrepreneurs, Activists, Funders, Politicians, and Everyone in between. Machynlleth: Public Interest Research Centre.

Humes, Cynthia. 2005. "Maharishi Mahesh Yogi: Beyond the TM Technique." In Gurus in America, edited by Thomas Forsthoefel and Cynthia Humes, 55–79. Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

Huntington, C. W. 2015. "The Triumph of Narcissism: Theravada Buddhist Meditation in the Marketplace." Journal of the American Academy of Religion 83 (3): 624–648.

Huppert, Felicia, and Daniel Johnson. 2010. "A Controlled Trial of Mindfulness Training in Schools: The Importance of Practice for an Impact on Well-being." The Journal of Positive Psychology 5 (4): 264–274.

Huxley, Aldous. 1932. Brave New World. London: Chatto & Windus.

Ingram, Daniel. 2008. Mastering the Core Teachings of the Buddha: An Unusually Hardcore Dharma Book. London: Aeon Books.

Kabat-Zinn, Jon. 1994. Wherever You Go, There You Are: Mindfulness Meditation in Everyday Life. New York: Hyperion.

Kabat-Zinn, Jon. 1998. "Toward the Mainstreaming of American Dharma Practice." In Buddhism in America, edited by Brian Hotchkiss, 478–528. Boston, MA: Tuttle Publishing.

Kabat-Zinn, Jon. 2005. Coming to Our Senses: Healing Ourselves and the World through Mindfulness. New York: Hyperion.

Kabat-Zinn, Jon. 2009. "Foreword." In Clinical Handbook of Mindfulness, edited by Fabrizio Didonna, xxv–xxxii. New York: Springer.

Kabat-Zinn, Jon. 2011. "Some Reflections on the Origins of MBSR, Skillful Means, and the Trouble with Maps." Contemporary Buddhism 12 (1): 281–306.

Kabat-Zinn, Jon. 2015. "The Deeper Dimensions of Mindfulness – Jon Kabat-Zinn." The Mindfulness Summit, October 31, 2015. https://themindfulnesssummit.com/sessions/jon-kabat-zinn.

Kelsey-Fry, Jamie, and Anita Dhillon. 2010. The Rax Active Citizen Toolkit: GCSE Citizenship Studies Skills and Processes. Oxford: New Internationalist.

Kuyken, Willem, Katherine Weare, Obioha Ukoumunne, Rachael Vicary, Nicola Motton, Richard Burnett, Chris Cullen, et al. 2013. "Effectiveness of the Mindfulness in Schools Programme: Non-randomised Controlled Feasibility Study." The British Journal of Psychiatry 203: 126–131.

Kuyken, Willem, Rachel Hayes, Barbara Barrett, Richard Byng, Tim Dalgleish, David Kessler, Glyn Lewis, et al. 2015. "Effectiveness and Cost-effectiveness of Mindfulness-based Cognitive Therapy Compared with Maintenance Antidepressant Treatment in the Prevention of Depressive Relapse or Recurrence (PREVENT): A Randomised Controlled Trial." The Lancet 386 (9988): 63–73.

Lam, Raymond. 2015. "Conscientious Compassion: Bhikkhu Bodhi on Climate Change, Social Justice, and Saving the World." Tricycle: Trike Daily, August 20. http://tricycle.org/trikedaily/conscientious-compassion.

MAPPG. 2015. Mindful Nation UK: Report by the Mindfulness All-party Parliamentary Group. London: The Mindfulness Initiative.

McKibben, Bill. 2016. "A World at War." New Republic, September, 22–31.

Mindfulness in Schools Project. 2016. "Teachers' Notes." Eleven-part Course-book and Slides for 2015–16, plus "Student Workbook," Available online. Accessed June 6, 2016. https://mindfulnessinschools.org/members/login.

Monbiot, George. 2016. "Neoliberalism – The Ideology at the Root of All Our Problems." The Guardian, April 25, 19.

Ñanamoli, Bhikku, and Bhikkhu Bodhi, trans. 1995. The Middle Length Discourses of the Buddha: A New Translation of the Majjhima Nikaya. Boston, MA: Wisdom Publications.

National Union of Students. 2016. "Double Jeopardy: Assessing the Dual Impact of Student Debt and Graduate Outcomes on the First £9K Fee Paying Graduates." NUS, August 17. http://www.nusconnect.org.uk/resources/double-jeopardy.

Nyanaponika, Thera. 2014. The Heart of Buddhist Meditation: The Buddha's Way of Mindfulness. 3rd ed. San Francisco, CA: Weiser Books.

Purser, Ron, and David Loy. 2013. "Beyond McMindfulness." The Huffington Post, July 1. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/ron-purser/beyond-mcmindfulness_b_3519289.html.

Rahula, Walpola. 1974. What the Buddha Taught. Rev. ed. New York: Grove Press.

Reveley, James. 2016. "Neoliberal Meditations: How Mindfulness Training Medicalizes Education and Responsibilizes Young People." Policy Futures in Education 14 (4): 497–511.

Rhys Davids, T. W., ed. 1910. Dialogues of the Buddha, Part II. London: Henry Frowde.

Ricard, Matthieu. 2015a. "Caring Mindfulness." The Huffington Post, April 22. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/matthieu-ricard/caring-mindfulness_b_7118906.html.

Ricard, Matthieu. 2015b. Altruism: The Power of Compassion to Change Yourself and the World. New York: Little, Brown and Company.

Rozman, Deborah. 1994. Meditating with Children: The Art of Concentration and Centering. 2nd ed. Boulder Creek: Planetary Publications.

Segal, Zindel, Mark Williams, and John Teasdale. 2013. Mindfulness-based Cognitive Therapy for Depression. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford.

Seligman, Martin. 2011. Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-being. New York: Free Press.

Sharf, Robert. 1995. "Buddhist Modernism and the Rhetoric of Meditative Experience." Numen 42 (3): 228–283.

SoulPancake. 2013. "An Experiment in Gratitude: The Science of Happiness." YouTube Video. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oHv6vTKD6lg.

Stanley, Elizabeth. 2010. "Neuroplasticity, Mind Fitness, and Military Effectiveness." In Bio-inspired Innovation and National Security, edited by Robert Armstrong, 257–279. Washington, DC: National Defense University Press.

Stanley, Elizabeth. 2014. "Cultivating the Mind of a Warrior." Inquiring Mind 30 (2): 16, 31.

Stanley, Elizabeth, and John Schaldach. 2011. "Mindfulness-based Mind Fitness Training (MMFT)®." mind-fitness-training.org, January. http://www.mind-fitness-training.org/MMFTOverviewNarrative.pdf.

Tan, Chade-Meng. 2012. Search inside Yourself: The Unexpected Path to Achieving Success, Happiness (and World Peace). New York: HarperCollins.

Tolle, Eckhart. 2005. The Power of Now: A Guide to Spiritual Enlightenment. London: Hodder and Stoughton.

Wallace, Alan. 2008. "A Mindful Balance: What Did the Buddha Mean by 'Mindfulness'?" Tricycle 18 (3): 60–63, 109–11.

Walshe, Maurice, trans. 1995. The Long Discourses of the Buddha: A Translation of the Digha Nikaya. Boston, MA: Wisdom Publications.

Wilson, Jeff. 2014. Mindful America: The Mutual Transformation of Buddhist Meditation and American Culture. New York: Oxford University Press.

Wilson, Jeff. 2016. "The Religion of Mindfulness." Tricycle 26 (1): 91–92, 120.

Zinn, Howard. 2002. You Can't Be Neutral on a Moving Train: A Personal History of Our Times. 2nd ed. Boston, MA: Beacon.

Further Reading

This article adapts a master's dissertation (part of my MA in Traditions of Yoga and Meditation from SOAS, University of London). ↩

See Hazeley and Morris (2015) in the appended reference list, p.6 and p.24. ↩

MAPPG (2015), p.7 and p.10. ↩

MAPPG (2015), p.9 and p.71. ↩

MAPPG (2015), p.29. ↩

MAPPG (2015), p.61. ↩

Purser and Loy (2013). ↩

Quotations from MiSP materials are from the 2015–2016 edition of the dot-b syllabus (Mindfulness in Schools Project 2016). The course has nine lessons, plus an introductory class. There are also guidelines for staff and a student workbook. All documents and slides are available online to MiSP-trained teachers. ↩

See Felver and Jennings (2016), and Felver et al. (2016). ↩

Kabat-Zinn (1994), p.4. ↩

Satipatthana Sutta (MN I.55-63) and Maha-Satipatthana Sutta (DN II.290-315). See Ñanamoli and Bodhi (1995), pp.145-155 and Walshe (1995), pp.335-350. ↩

MN I.56, trans. Gethin (2008), p.143. ↩

MN III.78-88, trans. Ñanamoli and Bodhi (1995), pp.941-948. ↩

Gethin (1998), p.82. ↩

Bodhi (2011), p.31. ↩

The concepts are frequently linked, for example in SN IV.210-214. See Bodhi (2000), pp.1265-1269. ↩

Rhys Davids (1910), p.322. ↩

Bodhi (1994), p.96. ↩

Bodhi (1994), p.82. ↩

Sharf (1995). ↩

DN I.12, trans. Walshe (1995), p.73. ↩

DN I.165, trans. Walshe (1995), p.152, and MN I.447, trans. Ñanamoli and Bodhi (1995), p.550. ↩

AN II.95, trans. Bodhi (2012), pp.476-477. ↩

Gethin (1998), p.229. ↩

Kabat-Zinn (2011), p.283. ↩

Kabat-Zinn (2011), p.283. ↩

Kabat-Zinn (2011), pp.290-291. ↩

Kabat-Zinn (1998), p.520. ↩

Kabat-Zinn (2011), p.298. ↩

Cohen (2006), p.11. ↩

Nyanaponika (2014), pp.17-18. ↩

Bodhi (2011), p.30. ↩

Wallace (2008), p.60. ↩

Bodhi (2011), p.27. ↩

Goldstein (1976), pp.20-23. ↩

Rahula (1974), p.72. ↩

Hanh (1976), p.61. ↩

Braun (2013). ↩

Wilson (2014), p.19. ↩

Wilson (2014), p.128. ↩

Tan (2012), p.235. ↩

Huntington (2015), p.632. ↩

Kuyken et al. (2015), pp.63-73. ↩

Segal, Williams, and Teasdale (2013), p.43. ↩

Huppert and Johnson (2010), p.270. ↩

Kuyken et al. (2013), pp.129-130. ↩

Mindfulness in Schools Project (2016). ↩

Bailey (2014), p.30. ↩

Interview with Chris Cullen, 11 July 2016. Cullen no longer works for the MiSP due to other commitments outside schools. ↩

Presentation by Mark Williams at MiSP conference in London, 22 January 2016. ↩

Rozman (1994) and Erricker and Erricker (2001). ↩

Humes (2005), p.66. ↩

Farias and Wikholm (2015), pp.56-58. ↩

Brown (2016), p.64. ↩

Wilson (2016), p.120. ↩

Burnett (2011), p.98. ↩

Kabat-Zinn (2005), p.95. ↩

Burnett (2011), pp.103-106. ↩

Burnett (2011), p.112. ↩

Burnett (2011), p.100. ↩

MAPPG (2015), p.29. ↩

Burnett (2011), p.113. ↩

Segal, Williams, and Teasdale (2013), pp.140-143. ↩

Kabat-Zinn (2015). ↩

Stanley and Schaldach (2011), p.2. ↩

Stanley (2010), p.263. ↩

Stanley (2014), p.16. ↩

Interview with Daniel Ingram, 16 July 2016. ↩

Ricard (2015a). ↩

Ricard (2015b), p.259. ↩

SoulPancake (2013). ↩

Dweck (2006), p.7. ↩

Seligman (2011), p.17. ↩

Email correspondence, 15 July 2016. ↩

Burnett (2011), p.94. ↩

MN I.190-1. See Ñanamoli and Bodhi (1995), p.283. ↩

Kabat-Zinn (1994), p.74 and p.xv. ↩

Gates and Senauke (2014), p.15. ↩

Interview, 16 July 2016. ↩

MN I.167, trans. Ñanamoli and Bodhi (1995), p.260. ↩

Hanh (1999), pp.221-222. ↩

Hanh (1999), pp.128-135. ↩

Hanh (1976), p.42 ↩

Buddhadasa (2002), p.22. ↩

Dunne (2011), p.75. ↩

Tolle (2005), pp.9-13. ↩

Hay (1987), p.217. ↩

MAPPG (2015), p.69, p.21 and p.7. ↩

Chomsky (1989), p.viii. ↩

Kabat-Zinn (2005), p.508. ↩

Holmes, Blackmore, and Hawkins (2011) and Kelsey-Fry and Dhillon (2010). ↩

Monbiot (2016). ↩

Connolly (2013), p.53. ↩

Reveley (2016), p.507. ↩

McKibben (2016). ↩

Eaton (2013). ↩

Kabat-Zinn (2005), p.564. ↩

Zinn (2002), p.24. ↩

See National Union of Students (2016) and Department for Education (2016). ↩

Forbes (2015). ↩

Huxley (1932), p.121. ↩

Kabat-Zinn (2005), p.500-580. ↩

Foreword to MAPPG (2015), p.9. ↩

Kabat-Zinn (2009), p.xxviii. ↩

MAPPG (2015), pp.29-31. ↩

Burnett (2011), p.85 and p.106. ↩

Forbes (2016), p.1267. ↩

Lam (2015). ↩